An eventful 2020 in the former Soviet Union – with political crises in Belarus and Kyrgyzstan and a war in Nagorno-Karabakh – provides an opportunity to assess the future role of the dominant regional actor Russia, and what other forces are determining the stability and operational challenges across Eurasia in 2021.

- Russia’s political, security and economic leverage persists in the region, and it will likely continue to enjoy cordial – if not positive – relations with most former Soviet countries.

- However, Turkey is emerging as an increasingly dominant player and partner in the Caucasus and Central Asia, especially with regards to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

- Meanwhile, even where Russia remains the undisputable key ally to a country – such as Belarus – social and cultural changes are taking place independent of Russia that will complicate Russia’s ability to manage regional crises.

- Operators when seeking to prepare for and anticipate events in the post-Soviet space should increasingly consider a diverse range of relationships and triggers.

Back in the USSR

Thirty years have now passed since the Soviet Union collapsed, and any characterisation of the region that refers to the former Soviet state – former Soviet Union, post-Soviet space – seems increasingly anachronistic to many Kazakhstanis, Azerbaijanis and Belarusians who have been born since 1991. Viewing the region as a collective bloc has endured over the last three decades mostly because Russia, by far the largest economy of all the former Soviet states, has maintained unparalleled political, economic, military and in some cases cultural influence over the other states. However, these countries’ relations with Russia are no longer consistently the key determinant of their political, social and economic trajectory. As the events of 2020 and the first few months of 2021 have demonstrated, for operators in the region, understanding risks in the former Soviet Union increasingly requires a broader frame of reference.

Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire: Russia the “winner”?

Among the most significant events of 2020 to take place in Eurasia was a six-week war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. A conflict that had been effectively frozen since the early 1990s came to life after Azerbaijan launched a major offensive to gain control over territories that Armenia had overseen since 1994. Russia, long a key mediator of the conflict thanks to maintaining good relations with both sides, brokered the ceasefire that brought the six-week war to an end in November 2020. As part of the ceasefire deal, for the first time since the fall of the Soviet Union Russia secured a place for 5,000 of its troops as peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh for a period of five years.

At first glance, Russia appears to be a clear “winner” in the conflict, and its instrumental role in determining the outcome of a major regional crisis seems assured. However, Russia was in fact taken by surprise by Azerbaijan’s offensive, and took several weeks to come up with any kind of a response. Crucially, the Azerbaijani offensive was only made possible by the increasingly assertive presence in the region of another player: Turkey. Increasing Turkish military and political support for Azerbaijan over the last few years was what emboldened Azerbaijan to attempt – and succeed – in changing the map in the conflict region for the first time in nearly 30 years. While Turkey’s poor relations with Armenia prevented it from playing a neutral arbiter role as Russia did, its newfound influence over the conflict and therefore the South Caucasus region is in no doubt. Any major new shift in the conflict dynamics may be overseen by Russia, but it will not take place without Turkey’s approval and political and military input.

Multi-vector foreign policies in Central Asia

Turkey is also of growing importance in the five former Soviet states of Central Asia. Long touted as a potential source of alternative support thanks to its shared linguistic and cultural heritage with Turkic-speaking Central Asian countries, Turkey has never had the same influence in the region as Russia or China. However, Central Asian states have always been keen to balance their powerful neighbours and diversify their trade and security alliances where possible. Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu visited three of former Soviet Central Asian countries in early March and was warmly welcomed.

While Turkey has little prospect of dislodging Russia as the region’s main political backer in the two-year outlook at least, the desire of both Turkey and the Central Asian states to increase Turkey’s role in the region underscores that forces beyond Russia should be considered when examining developments in these countries. Meanwhile, China continues to increase its economic and military involvement in the region, though has negligible prospects of having a prominent political or cultural role.

Central Asia is of course a region in its own right, too. Uzbekistan is a key example of this. Since it embarked on a major economic reform programme in 2016 it has been carving a role for itself as a co-leader of the Central Asia region alongside Kazakhstan. While maintaining good relations with Russia is key, Uzbekistan is cultivating close relations with China, Turkey and Afghanistan, and through improving regional transport and trade links generating a more credible Central Asia regional identity independent of Russia and the Soviet legacy.

What sort of relationship should your country seek with other countries?

Surveys of 1,000 people aged between 14-29 years in each country conducted 2015-17. No data on Turkey.

Kyrgyzstan, a much less economically independent state than Uzbekistan, also saw major events take place in 2020 without Russia playing a central role. Post-election protests in Kyrgyzstan in October 2020 were effectively hijacked by a low-profile, imprisoned MP, who through alleged intimidation of parliamentarians installed himself as interim prime minister and president, before securing a full presidential term in January 2021 through a snap election. Political unrest of this kind is not new in Kyrgyzstan, but in contrast with previous instances, Russia on this occasion appeared to play a minimal role in determining the outcome. In a small but notable development, when new Kyrgyzstani President Sapyr Japarov met Uzbekistani President Shavkat Mirziyoyev on 13 March for the first time, they spoke Kyrgyz and Uzbek to each other – mutually intelligible Turkic languages, rather than Russian, typically the regional lingua franca.

Belarus

Of all the regional events to stand out in 2020, the emergence of a major, peaceful anti-government movement in Belarus is probably the most remarkable. A homegrown pro-democracy movement, neither funded nor instigated by any external forces, broke out in one of the region’s most politically restrictive and Russia-dependent nations. However, with highly unpopular President Alexander Lukashenko and the population having been in a stand-off for more than six months, it is undeniable that Russia is the key determinant of when and how Lukashenko leaves power. Belarus’ economic dependence on its large neighbour is such that Russia will have to sanction any new leader to make their ascent to the presidency possible. Russia’s priority is for Belarus to remain in Russia’s sphere of influence, and out of the EU and NATO.

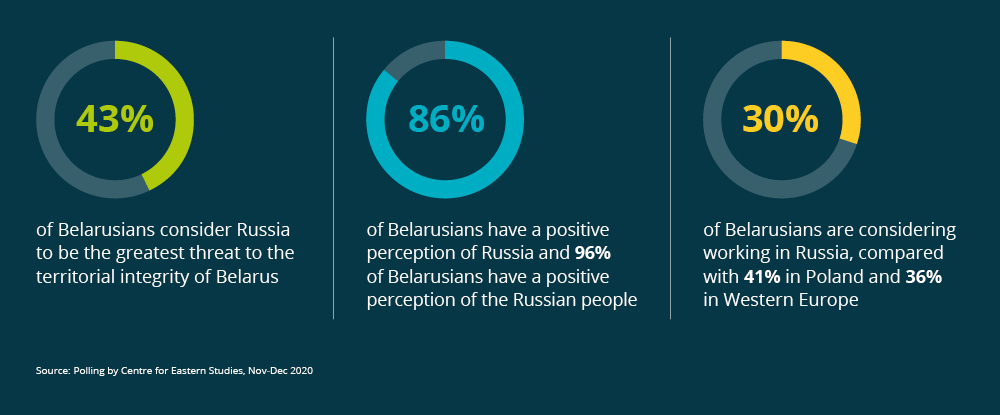

Nonetheless, there are forces at play in Belarus that Russia is ill equipped to control. In part, this is because there is no pro- and anti- Russia narrative fuelling the pro-democracy movement for Russia to tap into. As a new, internet-savvy generation of people with few memories of and little nostalgia for the Soviet Union comes of age, the social trends and forces determining the demands that the population makes are becoming more complex and arguably more difficult for Russia to manage. While Russia will be pivotal in determining how any fresh elections take place, it is far from assured that the population will accept the candidate or arrangement that Russia puts forward.

Regional leadership?

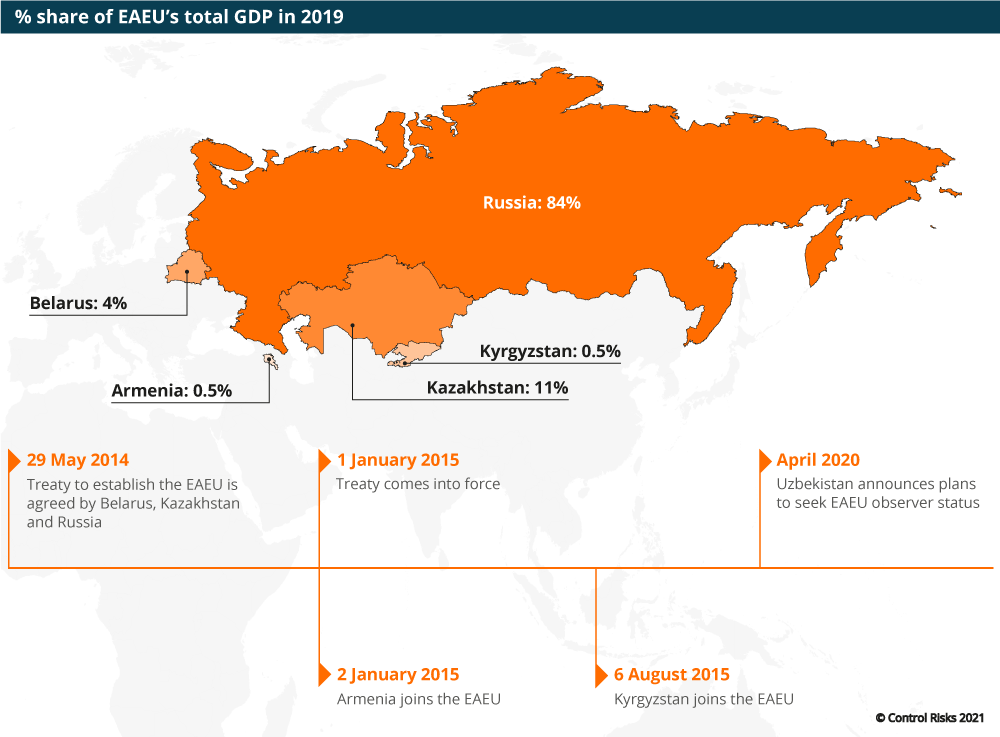

Meanwhile, formal integration initiatives by Russia in a region that it perceives as its sphere of influence are looking weak. The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) came into existence in 2015 at the instigation of Russia. It encourages free movement of goods and services and provides for common policies in various economic spheres. Since the bloc’s inception, Russia’s disproportionate economic weight has been starkly apparent, and created considerable unevenness in mutual trade and associated policies. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fundamental limitations in the EAEU’s ability to facilitate swift, pan-regional responses or ensure that trade flows continue among its members during crises.

More complex risk outlook

A number of social changes in the region are also taking place that either are not related to developments in Russia or that are illustrating a move away from Russian dominance. For example, on International Women’s Day on 8 March 2021, there was a record level of women’s rights marches and demonstrations across the region, suggesting that pressure for social change is emerging. Meanwhile, a rural exodus to cities in many countries has seen an increase in the use of native languages over Russian – the traditional language of the educated elites and in the cities. Government-led transitions from the Cyrillic to Latin alphabets for local languages in several Central Asian countries are also weakening some of the traditional symbolic links to Russia.

There is little doubt that Russia will retain an unparalleled leverage over the region thanks to decades of recent shared history and economic ties. For the most part, attitudes of people across the former Soviet Union towards Russia and Russians remain favourable, if not very warm. However, for businesses and organisations operating across this vast region, understanding Russia’s attitudes and priorities in relation to a former Soviet country is no longer sufficient to prepare for risks in that country, be it war, civil unrest, or political instability. The risk environment in the former Soviet Union is increasingly the product of multiple relationships and cultural and social influences.