The African Development Bank (AfDB) on 20 May announced the establishment of a new USD 1.5bn financing facility to help tackle food insecurity on the continent amid growing concerns over the socioeconomic impact of rising global food and fuel prices.

Commodity crunch

AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina said that the facility would help to bridge the continent’s food security gap and build progress towards Africa’s self-sufficiency. The launch of the fund came amid growing concerns over global food supplies, with the IMF on 24 May estimating that food prices will increase by 14% in 2022. The increase is largely due to disruption to global food supplies brought about by the conflict in Ukraine, given that many countries import large proportions of their grain supplies from Eastern Europe.

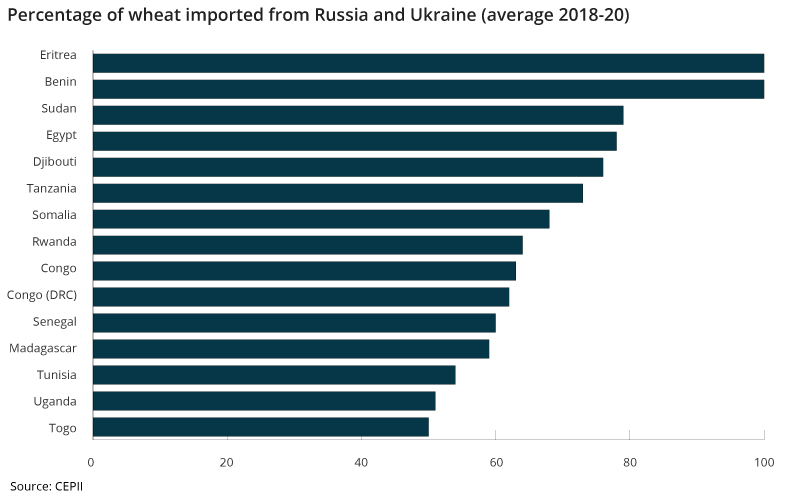

However, even if the AfDB deploys the new fund quickly, it will do little to immediately address the imminent food security challenges facing African governments. North African countries, which rely on Ukrainian and Russian imports for the majority of their wheat imports, have been hit particularly hard. For example, in 2021 Russia and Ukraine accounted for 50% and 30% of Egyptian wheat imports respectively. Meanwhile, Tunisia sources 50% of its wheat from Ukraine.

The picture in sub-Saharan Africa is more mixed. Although many sub-Saharan African countries also rely on wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine, maize is the more common staple. This means that, though the price of bread is increasing, households are better able to weather the storm as they reduce their purchases of bread.

But there are additional considerations. Countries such as Cameroon, Ghana, Senegal and Kenya import substantial amounts of fertiliser from Russia, one of the world’s largest exporters of potash. Disruption to fertiliser supply chains is driving a rise in the cost of food production at a time when households can ill afford it. As an important producer of vegetable (sunflower) oil, supply chain disruption in Eastern Europe has also directly increased food costs in Kenya, South Africa and Egypt, where households are particularly reliant on vegetable oil imports.

Moreover, the impact of the Ukraine conflict on oil prices has also had far-reaching consequences. The IMF expects the annual average price of oil to settle at USD 107 per barrel in 2022, up USD 38 from 2021. As net oil importers, most African economies are likely to take an additional hit from the resultant fuel price rises.

Eating into incomes

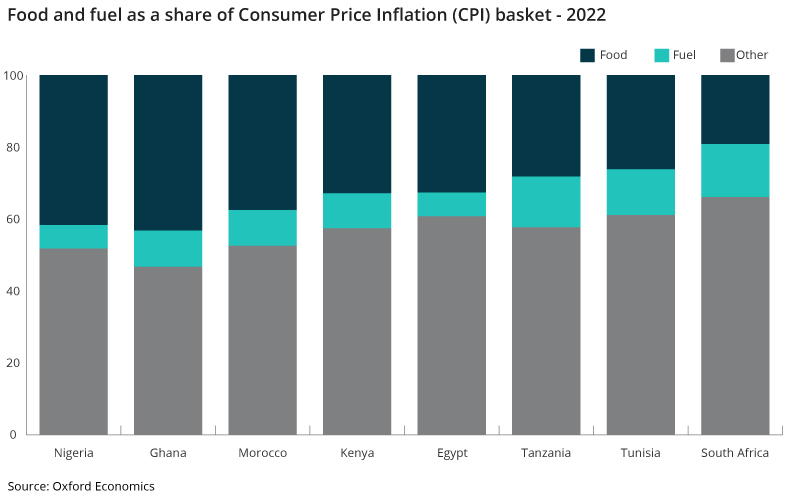

The cumulative impact of this has been to drive a rise in inflation across the continent, eroding the gains from a slow recovery from the COVID-19-induced economic downturn. As food and fuel comprise a large proportion of household spending, African governments have been forced to take extraordinary fiscal measures to cushion their populations.

Most government responses have focused on introducing or delaying the phasing out of state subsidies. For example, Kenya in April introduced subsidies on fertiliser and, contrary to IMF advice, retained a fuel subsidy to prevent a drastic hike in fuel prices in May. Egypt now plans to purchase more wheat locally, aiming to reach 60% grain self-sufficiency by the end of 2022. But to do so it has had to increase the price it will pay for local wheat by 13% this year to encourage local production. The Tunisian government has also been purchasing wheat at record high prices. Meanwhile, Zambian Minister of Energy Peter Kapala on 26 May said that the government will consider extending tax waivers on fuel beyond a 30 June deadline agreed with the IMF in a bid to prevent further increases in inflation.

However, governments are unlikely to be able to sustain these payments for extended periods. Levels of public debt on the continent were already high and rising amid a drive to bridge the infrastructure deficit. Egypt and Tunisia have high debt-to-GDP ratios at 95% and 87% respectively, while Kenya’s public debt is anticipated to reach 70% in the year ahead, according to the IMF. With the need to dedicate increasing portions of their income to debt repayments, such subsidy programmes are by necessity likely to be temporary.

Moreover, limited sources of domestic revenue will place further constraints on governments. Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo on 1 May said that removing taxes on petroleum products would cut government revenue by GHC 4bn (USD 516m), while Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni on 22 May said that subsidising food and fuel imports would mean a loss of more than UGX 3 trillion (USD 820m) in tax revenues. These dynamics will drive increasingly challenging socioeconomic conditions across the continent, with a particularly detrimental impact on lower-income, urban populations.

Finding this article useful?

Chomping at the bit

The inability of governments to shield their populations from the negative impact of rising inflation will continue to drive dissatisfaction with governments and support for opposition movements across Africa. In this challenging socioeconomic context, sporadic unrest is likely across the continent in the coming months.

In North Africa, governments will be keen to avoid the widespread protests that rises in bread, wheat and sugar prices have provoked in previous years. In Tunisia the authorities are facing unrest driven by socioeconomic grievances, and have launched operations to crack down on the hoarding of foodstuffs and black-market sales of commodities. Labour strikes have also been reported in Mauritania in recent weeks. Even in countries with traditionally more benign security environments, civil society and labour groups are likely to use rising inflation to mobilise protests, as seen recently in Mauritius and Senegal.

However, it is the countries undergoing transitions that will be most vulnerable as cost-of-living concerns exacerbate underlying frustrations with authorities. In Sudan, where the military took over in October 2021 citing the inability of civilian authorities to address socioeconomic grievances, weekly protests against the military continue given the failure of the military to follow through on its promises. Military-led regimes in Mali, Chad, Guinea and Burkina Faso will need to assure populations that they will improve living conditions, or they too are likely to face growing popular unrest. This is particularly the case in Mali, given limited government finances amid regional and international sanctions and lack of funding from external diplomatic actors.

High inflation is also likely to feature heavily in campaigning ahead of key elections in the coming year. In Kenya, the populist campaign of Deputy President William Ruto continues to attract voters facing increasingly challenging economic circumstances as he promises a widespread distribution of wealth. Angolan President João Lourenço and his ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) are also facing growing calls from the opposition and civil society to better address inequality ahead of elections in August. Nigeria faces a particularly turbulent election period as socioeconomic grievances continue to drive recruitment by bandit and militant groups in parts of the country.

Meanwhile, following a drawn-out election process in Somalia, incoming President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud will have to contend with the continued ability of Islamist militant group al-Shabab to exploit socioeconomic grievances to recruit from vulnerable populations across the country. As the Horn of Africa, and Somalia in particular, experiences one of the worst droughts in its history, al-Shabab will exploit the situation to intensify its campaign of attacks in a bid to undermine Mohamud’s administration.

Food for thought

Both public and private sector workers are likely to mobilise protests in the coming months to demand wage increases given rising inflation. Companies in urban areas will need to closely monitor public sentiment and related protest activity, particularly given that the tendency of security forces to respond to demonstrations with excessive force can lead to escalations in even peaceful protests. For example, cost of living concerns are likely to dominate in South Africa as unionised workers (such as miners and steelworkers) and employers begin their annual wage negotiations, with the so-called “strike season” likely to be particularly intense this year. Incidents of looting are likely during political and socioeconomic protests in urban areas, with food and fuel retailers in particularly vulnerable to being targeted by petty criminals.

Meanwhile, large operators, such as those in the mining and oil and gas sectors, will likely face heightened expectations to assist local populations as socioeconomic challenges bite. Companies will need to carefully manage these expectations or contend with work stoppages organised by local communities. Unrest related to artisanal mining is also likely to increase given limited employment opportunities, as seen at mine sites in Burkina Faso and Senegal in recent weeks.

When adding images copy the HTML this is in and alter the image. The image should always be 1000px wide.