Four key risk points:

1. Recent local elections have left Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) severely weakened, while opposition parties and rebel factions within the AKP are experiencing an awakening.

2. A likely power struggle over the coming years between the government and a strengthened opposition would increase political instability and heighten the risk of civil unrest.

3. The fractured political landscape is likely to increase unpredictability for businesses and complicate the implementation of badly needed economic reforms.

4. Although not our baseline scenario in the next two years, an increasingly credible alternative scenario sees cracks in the governing alliance giving a united opposition the power to call early elections, paving the way for government change.

Times are changing

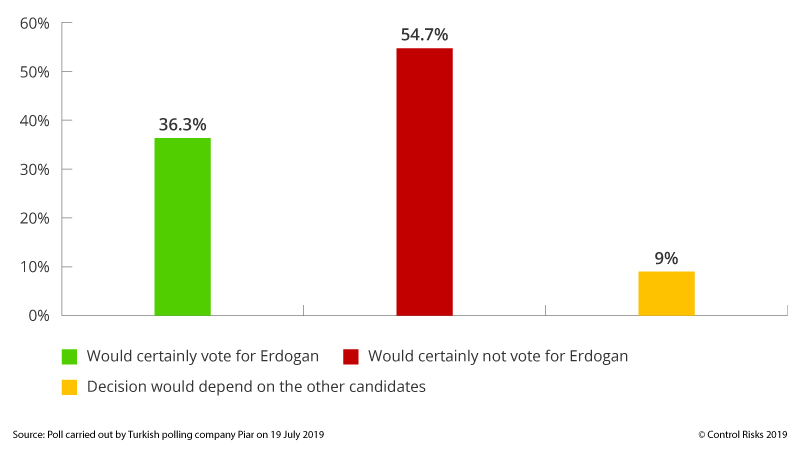

The opposition Republican People's Party (CHP)’s persuasive victory in the 23 June re-run of Istanbul’s mayoral elections marked an important milestone in Turkey’s political evolution and offers an alternative future vision of the country’s trajectory. Nearly a month later, a survey by Turkish polling company Piar on 19 July suggested that the government’s poor performance in the local elections was not just a one-off occurrence. Of those questioned in the poll, more than half stated that they would certainly not vote for Erdogan in a presidential election. It appears that the population is angling for political change.

Would you vote for Recep Tayyip Erdogan if a presidential election were held today?

The power of the municipalities

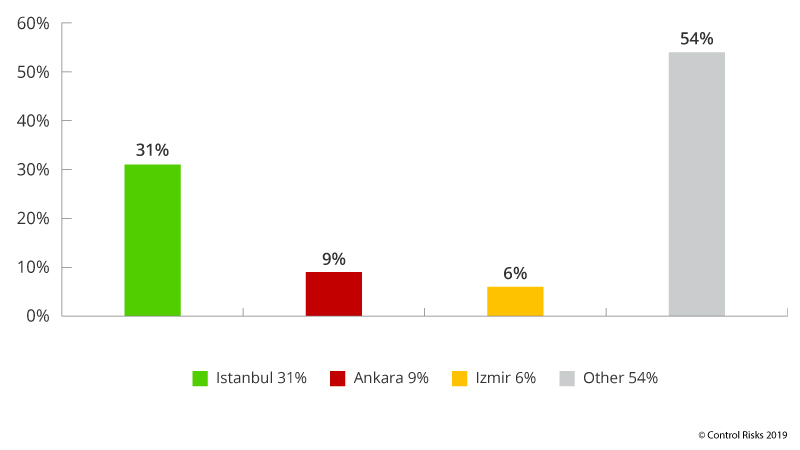

With the opposition now in control of five out of six of Turkey’s biggest urban centres, including the largest city Istanbul and the capital Ankara, the era of Erdogan’s unchallenged success in Turkish politics appears to be over. The election results show that while Erdogan has consolidated power on the national level, his support in major cities – the centres of innovation where large parts of Turkey’s national income is generated – is eroding.

Turkey’s large metropolises are autonomous administrative entities that manage huge financial resources. The 2019 budget for the Istanbul metropolitan municipality is 23.8bn Turkish lira (currency), the rough equivalent of USD 4.2bn. Control of these municipalities has placed significant power into the hands of the opposition, which now has the scope to present viable alternative candidates and alliances.

Three larges municipalities’ share in the country’s GDP for 2017

For the AKP, Istanbul has been a critical source of revenue to provide rent to government-friendly businesses. The opposition now has the opportunity to dismantle AKP patronage networks and restructure them after its own design, giving it considerable decision-making authority over public tenders, construction permits and land allocations.

However, the government is already pushing for a re-distribution of powers on the municipal level, likely an attempt to impede the opposition’s ability to govern effectively. New policies have been presented and are likely to be implemented that would allow the central government to take control of municipal fiscal policy.

Therefore, for businesses active in Turkey’s biggest cities, the upcoming two-to-three years will be marked by conflicts over decision-making. With authority over municipal-run enterprises reallocated since the 23 June election to district councils under AKP control, but authority to decide over municipal tenders now in the hands of the opposition, business-critical processes are likely to be increasingly marred by institutions under opposing control.

Decision-making will be markedly fissured and collaboration with local partners that either have close relations to the governing party or clear alliances with the opposition will both have the potential to create issues for gaining access to tenders and permits. Overall, this ambiguous landscape will increase the threat of corruption, particularly in interactions with local-level government officials.

National-level defeats

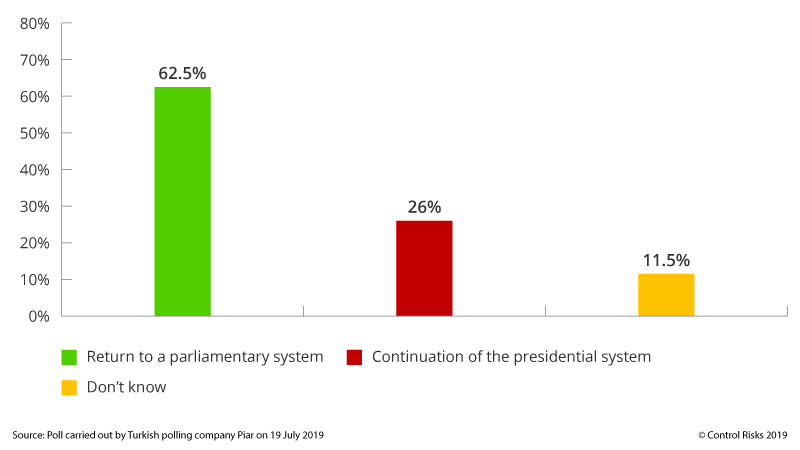

On the national level too, new alliances are taking their toll on Erdogan and the AKP. Despite the extended institutional powers that Erdogan granted himself in 2018 through the introduction of a super-presidential constitution, Erdogan appears increasingly weakened politically. The Piar poll from 19 July suggests that large parts of the population no longer regard the presidential system, introduced by a popular referendum only a year ago, as in the country’s best interest.

The presidential system has been in place for one year. If a referendum was held on the continuation of the presidential system, how would you vote?

Despite being ideologically heterogeneous, the tacitly aligned opposition has been held together by a common denominator: the rejection of Erdogan’s rule. This has successfully aligned parties from opposing ends of the political spectrum including the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP) and the right-wing nationalist Good Party (IYI). The opposition’s coherence is gaining strength as it consolidates around its unprecedented success in the recent elections, and as such will be difficult to halt.

Fatigue over the country’s divisive and repressive politics is also tangible within the AKP. It has also alienated a considerable part of its voter base, illustrated by opposition candidate Ekrem Imamoglu’s comfortable win in the June re-run of the Istanbul election, following the government-influenced annulment of the initial March vote. A split of the AKP appears inevitable at this point and would further weaken its position.

A drawn-out power struggle

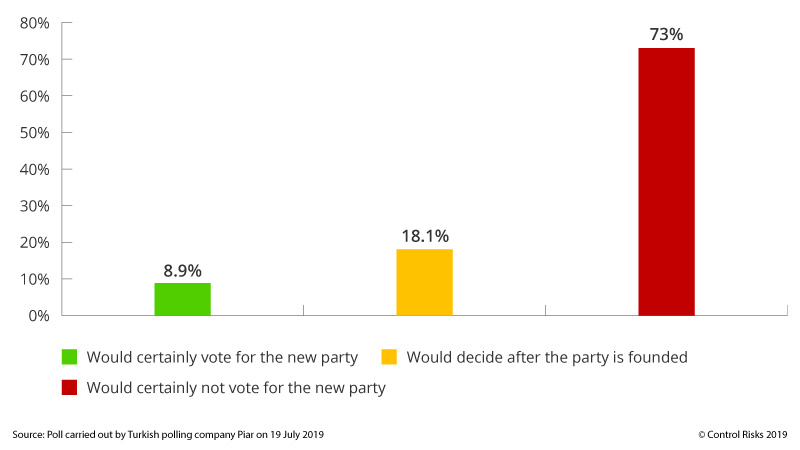

The above-mentioned Piar poll suggests that AKP defectors and splinter parties will lead to considerable electoral losses for the AKP. New parties have been announced by former deputy prime minister (2009-15) and founding member of the AKP Ali Babacan, former president Abdullah Gul (2007-14) and former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu (2014-16). Babacan’s party in particular is showing signs of success, even before it has been officially launched (see below graph).

Would you vote for a party established under the leadership of Ali Babacan?

This fissure leads us to believe that the AKP-Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) alliance is likely to lose its parliamentary majority in the coming six months. Nonetheless, even under this scenario, the presidential system leaves little room for early elections. Given Erdogan’s diligent placement of loyal followers in parliamentary positions, the necessary super-majority of 60% in favour of a motion to call for early elections seems an insurmountable feat, for now. Therefore, a long, drawn-out power struggle remains likely, solidifying tensions as political pressures remain unrelieved until elections scheduled for 2023.

Rising political instability will bring with it a growing likelihood of civil unrest. Any increase in protests would likely be coined by the government as spurred on by Western meddling. In this scenario, foreign personnel and assets would face a greater threat of becoming the target of random violent assaults, especially in large cities.

Or could an early election be in the offing?

Erdogan’s political fortunes will likely depend on how he deals with the challenge of the resurgent opposition. So far, Erdogan has continued. facing these challenges by suppressing dissent and tightening control over key institutions, seeking to secure his grip on power. However, this approach has dampened his support, as has the centralisation of decision-making under the presidential system, which has removed a sorely needed process of expert deliberation.

The situation in Turkey is volatile. The country’s economic situation remains weakened, reforms have been stagnating and foreign policy is alienating Turkey from the West. Discontent as a result of these issues is felt by MPs of the AKP and the MHP alike; the AKP’s reduced support is likely to lead MHP MPs to question the value of their party’s relationship with the AKP in the coming years. These MPs would likely opt to join former MHP splinter party IYI, which is regarded as the anti-Erdogan alternative for right-leaning voters, or the CHP.

Although a drawn-out power struggle until the 2023 elections remains most likely, another course is gaining momentum. Control Risks regards a snowball effect of AKP and MHP defections, giving the opposition the necessary votes to call early elections, to be a credible scenario within the next two years. Especially in an environment of economic decline, such a scenario looks increasingly plausible, and could turn the tables for the opposition.