The race to secure critical mineral supply for the energy transition is facing a financing problem. While governments are increasingly putting their money where their mouth is, traditional commodities finance for mining companies has largely dried up since the pandemic. As spot prices for critical minerals remain subdued in early 2024, miners are increasingly turning to alternative sources of financing. These novel funding strategies present a way forward amid lacklustre economic conditions. However, these less conventional funding and investment structures mean that critical mineral investors will need to build resilience against the political and financial crime risks that are already manifesting as well as those that may be incubating.

State financing and intervention prosper

The critical minerals market is subject to significant state influence on both ends of the supply chain. Despite growing consumer demand for energy transition, this remains sluggish for certain associated commodities such as lithium. It is mainly state policies that are driving demand for more critical minerals supply and for more diverse and secure critical mineral supply chains. In the US the 2019 Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals and subsequent legislation, such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), aim to re-shore and friend-shore critical mineral supply chains. The EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, approved in December 2023, has similar aims.

National security concerns over supply chains risks are shared across the political spectrum, which means critical minerals policies are likely to persist regardless of political change. What’s more, these polices are increasingly backed by long-term funding commitments. There has been a rise in state-backed mining investment globally, most notably stemming from Asian and Middle Eastern countries such as China, South Korea, and the United Arab Emirates. G7 countries have put in place a range of funds, grants, and tax incentives to advance their strategic objectives, from Canada’s Critical Mineral Exploration Tax Credit to the IRA’s clean vehicle credit.

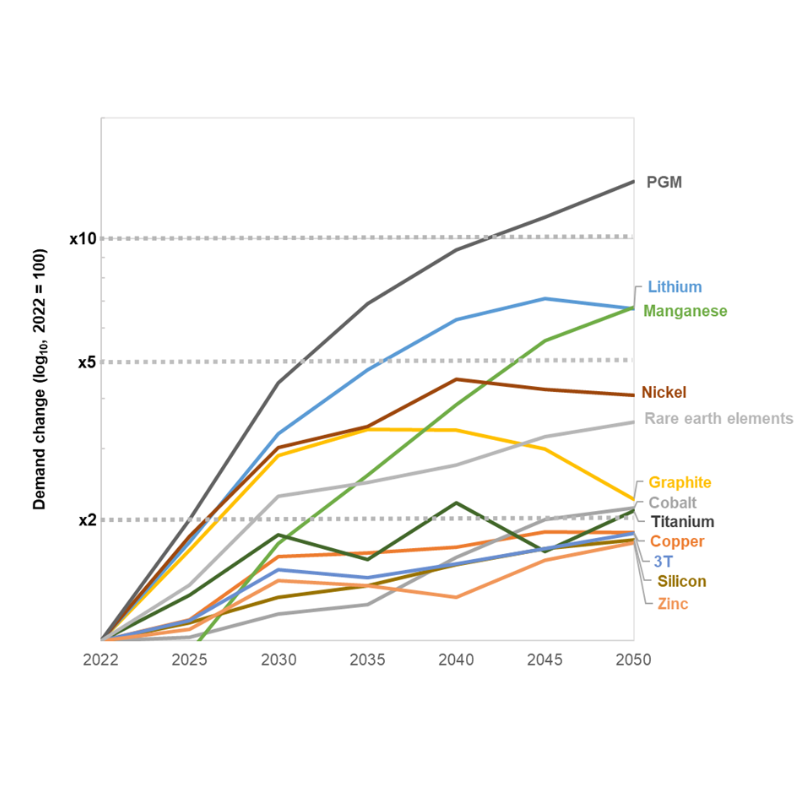

Figure 1: Indexed mineral demand for clean energy technologies - by mineral (current policies scenario, 2022-2050)

Source: IEA 2023; Critical Minerals Demand Dataset, https://www.iea.org, License: CC BY 4.0

Alternative financing flourishes

Despite this growing state support, the landscape for critical minerals financing remains challenging. Spot prices for key critical minerals – lithium, cobalt, copper, manganese, zinc, rare earths, and nickel – have dropped after a major uptick in 2021 and 2022. Even though they remain well above pre-2020 levels, miners are starting to see more pressure on project bankability, which in turn is constraining access to capital in the near term. Low commodity prices mean that critical minerals equities – notably in lithium and nickel – will be increasingly disadvantaged against existing supply from more profitable mines further down the cost curve. Juniors in particular will face hard decisions in the coming months.

The proliferation of critical mineral-focused mining juniors has also increased competition for this capital – mining IPOs continue to constitute a large proportion of new listings at the world’s major mining-focused exchanges. This worsened market status quo has meant that mine projects vital to the energy transition risk becoming uneconomical. A growing number of critical minerals companies are being put up for sale, taking out emergency financing, delaying project timelines and even entering administration due to financing constraints. While some governments have sought to respond with policy measures to shield critical minerals miners from bankruptcy, these will largely be stopgap solutions.

In these more difficult market conditions, mining companies have increasingly pursued alternative financing to capitalise their activities. There has been a notable rise in critical minerals focused royalties and streaming financiers, where mining companies offer a portion of future revenues in exchange for advance payment. There has also been an uptick in specialist mining private equity firms, which offer a more diverse portfolio to investors and in turn allow them to hedge risks.

As companies seek to secure their critical mineral supplies – motivated by the same considerations as governments and often to ensure compliance with government friend-shoring directives – they are providing new funding sources. Tech giants and electric vehicle manufacturers have spent the past few years getting more involved in their supply chains, from signing long-term offtake agreements directly with mines to directly investing in segments of the value chain.

Infrastructure roadblock

Beyond the more obvious financing requirements to allow for critical minerals extraction, there is also an increasing need for investment in supporting hard infrastructure such as railways, ports, and power generation. This is precisely the objective of the US and EU financing of the Lobito railway line, which will facilitate exports through the Atlantic of copper and cobalt from the Copperbelt in Zambia and the DR Congo.

Fit-for-purpose infrastructure can flip project viability but the challenge of low internal rate of return (IRR) remains. Critical mineral supply chains therefore desperately need a ramp up of multilateral, state, and private investment to fill the infrastructure gap and in turn accelerate the energy transition.

Emerging risks

The growing fundraising pressures on mining companies poses risks for investors. Most obviously, there is a greater incentive for mining companies to engage in fraud and other forms of impropriety to secure much-needed financial backing. Control Risks has supported clients in verifying a number of ownership, political exposure and financial crime risks related to obscure shell companies and special purpose acquisition companies (SPAC) in the sector.

On the other hand, state financing in the critical minerals market comes with strings attached. Global governments are concerned not just with increasing supply but with securing supply and, as a result, accessing such support will often entail restrictions on the partners and customers. Having a “foreign entity of concern” involved in a battery supply chain, for example, will render an electric vehicle ineligible for the clean vehicle credit in the US under the IRA. This emphasises the need for reliable and continuous intelligence on individual suppliers to ensure greater visibility and control over supply chains for operators.

More broadly, the demand for critical minerals has given leverage to the countries holding the resources. Global powers are increasingly in competition and pulling all diplomatic levers available to secure supply. Given the high demand, resource-rich countries in turn are increasingly emboldened in pursuing export bans and nationalisation. For example, in December 2022 Zimbabwe banned all lithium exports, and in June 2023 Namibia banned the export of unprocessed critical minerals; both moves being designed to encourage domestic processing. Chile and Mexico both decided to nationalise their lithium industries in 2023.