Amid President Xi’s emphasis on “common prosperity”, and a steady stream of regulatory interventions across multiple industries, recent news headlines have brought more fuel for fears about an anti-business backlash in China. State media republished an article by an outspoken nationalist blogger, criticising “big capital” and praising recent regulatory crackdowns, and we saw more portents of intensified antitrust scrutiny.

- The wave-making article and common prosperity mantra reflect a populist political current that is fuelling intensified regulatory enforcement, mostly based on existing policy goals.

- This will continue over the coming year, sustaining both domestic and foreign investors’ perceptions of increased political risk and uncertainty, as new firms and sectors are targeted.

- However, this is not a monolithic push to crush private business. Beijing wants the private sector to thrive in the long term, but will crack down where it sees specific risks or non-compliance.

- Enforcement shifts over time, but is not arbitrary or mysterious. It is partly predictable, based on government priorities like public welfare grievances, and perceived emerging or systemic risks.

- It is striking that foreign companies have not been a target of this year’s crackdown. This might not last. Many multinationals have significant exposure, notably to antitrust enforcement.

“Profound change”

It is unusual for multiple, authoritative state media outlets to give prominence to an article by a blogger who is not known to have any official affiliation or previous mainstream media presence, and has generally been seen as a rather outspoken nationalist or “leftist” voice. The republished article has thus made waves among China-watchers, given its content. It accuses celebrities and “big capital” of “worshipping the US”; says that a “profound change or revolution” is underway in the economy, finance, culture and politics, and praises the government for “combating chaos” with recent regulatory actions.

The author links all this with “common prosperity”. The term featured in Xi’s 17 August speech in which he reiterated a commitment to tackle income inequality, and called on wealthy people and companies to make greater social contributions. Within days, top e-commerce and technology companies had announced huge social donations or initiatives. While some officials have stressed that the common prosperity concept is not about “attacking the rich”, there is still palpable insecurity among many in the ‘elite’, from tycoons and celebrities, to officials. Hangzhou, the provincial capital of Zhejiang and home to Alibaba, recently had its top leader removed amid corruption investigations, with officials told to disclose any “improper” business links. Zhejiang was recently dubbed a “common prosperity pilot zone”.

Capitalists in crosshairs?

While not necessarily “profound” in themselves, recent official signals have compounded concerns among both local and international investors about political and regulatory uncertainty. An early catalyst for these concerns was the late 2020 government intervention that derailed Ant Group’s planned IPO, which was expected to be the world’s largest. A litany of developments in 2021 have added to perceptions of a more interventionist and volatile regulatory environment, notably:

- Multiple regulators in July investigated leading ride-hailing firm Didi Chuxing, including over cyber and data security concerns related to its US IPO this year. It is also under scrutiny in relation to concerns about market competition and labour practices.

- Social media giants Bytedance and Weibo have sold small stakes to state-controlled entities. It is unclear what actual influence these stakes will give, but the moves are widely seen as seeking to comply with government policy and regulatory priorities.

- Regulators this year have issued penalties or restrictions in sectors including online gaming, technology, steel, entertainment, real estate, food delivery and after-school education.

- A top policy co-ordination group chaired by Xi met on 30 August, and stressed the importance of anti-monopoly work in relation to common prosperity – the latest of several indications that longstanding antitrust scrutiny may further intensify in the coming months.

Not so surprising

Perceptions of increased political risk and uncertainty are partly justified by these signs of a return to “campaign-style regulation”, and political dynamics driving tighter enforcement. Populist-tinged political pronouncements in recent months follow ambitious long-term national development plans unveiled in March, the ruling Communist Party of China’s (CPC) 100th anniversary in July, and come ahead of a five-yearly CPC national congress in late 2022 (at which Xi will almost certainly secure an unprecedented third term). These bring renewed momentum to implement key policies and manage risks, to show CPC effectiveness in addressing public concerns, and to further bolster Xi’s position ahead of the congress.

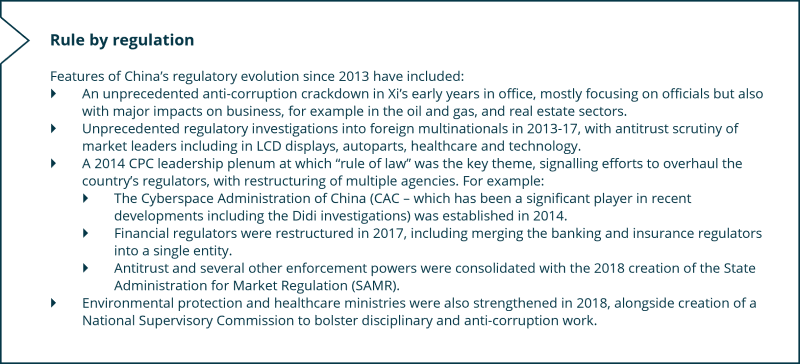

However, this is not a monolithic, general crackdown on private business. On the contrary, Beijing wants the private sector to grow strongly, but it is very willing to intervene where it deems that growth to be misaligned with priority policies or “national interests”. China has been carrying out various forms of “regulatory crackdown” for many years, and since 2013 has pursued a concerted strategy to revamp regulations, restructure regulators and tighten enforcement (see below). As well as strengthening top-down political control, a driving goal of these reforms is to create a better functioning market and business environment, and to better implement central policies – a perennial challenge for Beijing.

Crackdown breakdown

Regulatory developments in 2021 should be seen partly as the latest phase in this long-term trend. Instead, they are often conflated into one monolithic crackdown that has suddenly appeared, driven by political antipathy to business, with each move directed by an omnipotent Xi. This is misleading. Top-level political impetus certainly drives key trends, but when broken down to understand specific policy goals and industry dynamics, regulation looks much less arbitrary and rather more predictable.

Most uncertainty comes not from arbitrary attacks on business, but because in many cases enforcement involves relatively new issues, commercial dynamics. regulations or regulators. With some cyber and data regulation, for example, key players are sometimes “figuring things out as they go along”, amid multiple competing interests and agenda within the system.

What next?

Recent actions have been characterised by a focus on sectors including technology, internet firms and services. These will remain under scrutiny, but officials’ focus is not static. Assessing risks and exposure is usually best informed by focusing on the policies and issues driving enforcement, rather than by labelling certain sectors and companies as high or low risk. Companies’ prospects will fluctuate in most sectors as these dynamics play out. They therefore have to be assessed at that industry- and company-specific level. However, here are some key general considerations to help demystify the outlook:

- Any sector linked to “public welfare” or populist issues is exposed to scrutiny. The broad scope of this is reflected in the broad scope of enforcement from 2013 through 2021, targeting areas including healthcare, real estate prices, local pollution, food safety, labour practices, after-school education, and anti-competitive behaviour in multiple sectors.

- Any sector or company which Beijing sees as relevant to national security, stability or strategic interests is similarly exposed to intervention, especially for private companies or emerging risks where the state has not already established oversight of its target of concern. This is a factor in targeting of fintech and big data, but has also affected areas such as banking, food and energy.

- Any company that fails to grasp and fall in line with high-priority government policies or “guidance”, or that fails to comply with regulations on strategic or sensitive issues, is also potentially exposed. This has been a partial factor in some of the best-known events this year – notably involving the Ant and Didi IPOs – and the main factor in many more mundane cases, for example involving antitrust and environmental enforcement.

- To assess specific risks, it is important to differentiate between companies that Beijing might see as posing fundamental, strategic or systemic risks, and those that have been checked over specific behaviours and routine enforcement. In rare cases, whole sectors, activities or business models might be seen as undesirable. For example, parts of the private after-school education sector and certain highly polluting, low value-adding heavy industries may be in this category.

Foreigners not forgotten

Finally, it is worth remembering that in the first few years of “rule by regulation”, there were multiple instances of leading foreign multinationals being investigated and punished by Chinese regulators, involving several different enforcement issues and some major, landmark cases. There have been very few such cases in the last several years, even amid China’s disputes with other countries, and its proliferating legal framework for potential ‘retaliation’ (from the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law and Export Control Law, to the elusive Unreliable Entities List).

This probably reflects a deliberate choice by Chinese leaders to avoid any perceived broad attack on foreign business, which might cause a long-mooted – but so far absent – ‘exodus’ of foreign investors and multinationals. However, it would be a mistake to assume that this choice will hold indefinitely, or that it means foreign companies are not subject to the same regulatory scrutiny as Chinese companies. They are, particularly in areas like anti-monopoly and competition policy, where several risk factors intersect. Sooner or later, enforcement cases involving multinationals will return to the headlines.