This article is based on content originally published on our partner platform Seerist, the augmented analytics solution for threat and risk intelligence professionals.

After 13 years of civil war, the Assad regime collapsed in December 2024. Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has emerged as the dominant power, with various factions controlling different areas. The prospects for building a Syrian state depend on the territorial control and conflicting interests of key factions. What lies ahead?

- The political transition, dominated by HTS, will be protracted but likely marked by pragmatism and flexibility. A civil war among rebel groups remains broadly unlikely over the coming months.

- The HTS-led Syrian Ministry of Defence will centralise armed groups under its control, though larger factions will likely resist, seeking to maintain organisational independence.

- Although most actors support de-escalation, Türkiye’s ambitions to alter the status quo in northern Syria risk escalating conflict with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Front (SDF).

- Over the coming year, Control Risks’ political stability and war risk ratings for Syria will remain EXTREME, as significant uncertainty persists over HTS’s capability to durably stabilise the country.

Fragmented state

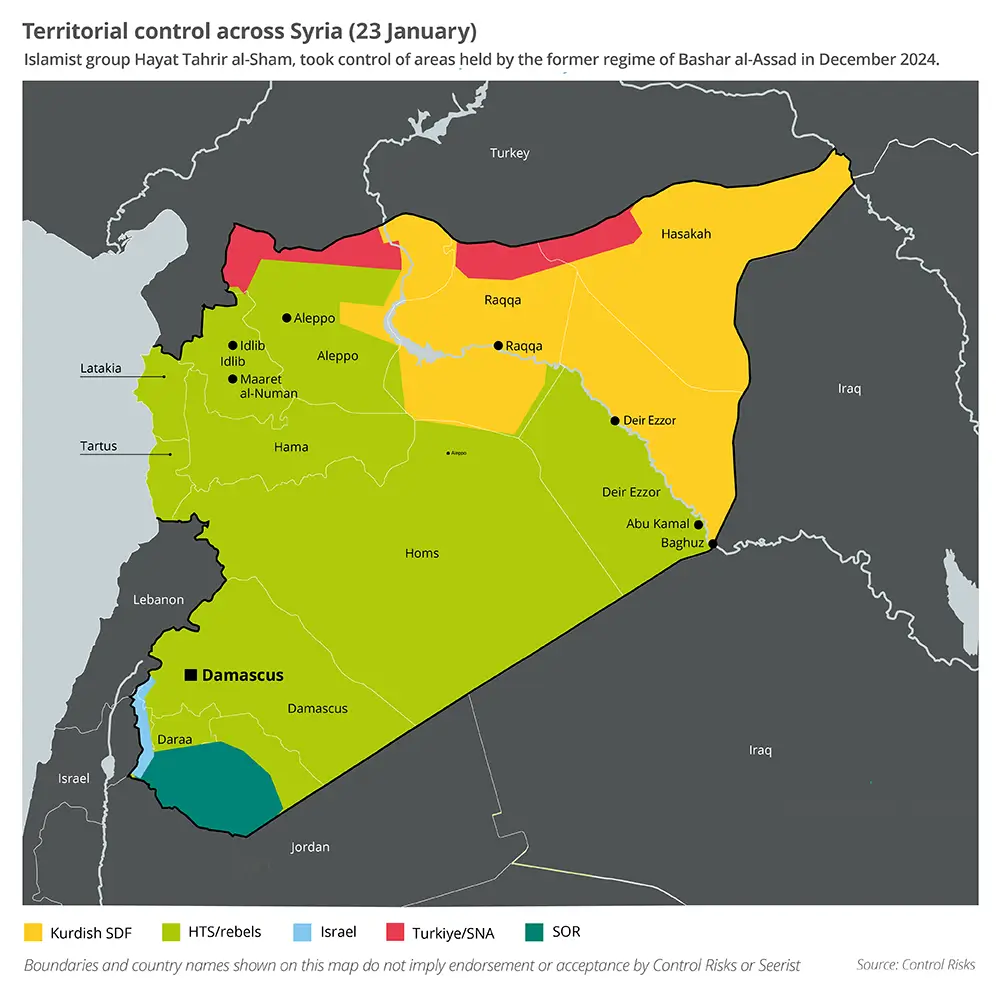

With the entire Syrian territory now under opposition control, four main power centres have emerged:

- HTS-led rebel Islamist factions control formerly regime-held areas seized during the November 2024 “Deterrence of Aggression” offensive, including Latakia, Tartous, Damascus, Homs, Hama, Idlib, large parts of Aleppo governorate and cities along the Euphrates River in Deir Ezzor governorate.

- In the south, Southern Operations Room (SOR) factions, allied with HTS, seized Daraa, Suweyda and Quneitra during the HTS-led offensive and dominate these governorates.

- The Kurdish-led and US-backed SDF holds the Raqqa and Hasakah governorates, the eastern countryside of Deir Ezzor and parts of the Aleppo countryside.

- Turkish-proxies of the Syrian National Army (SNA) maintain control over the northern border regions in Aleppo and Raqqa governorates and remain in conflict with the SDF.

New Syrian state

Following Bashar al-Assad’s fall, HTS emerged as the new ruling force in Syria and established an interim government. This governing body, primarily composed of officials from the Idlib-based Syrian Salvation Government, is due to remain in power in its current form until 1 March 2025. HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (also known by his nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Jolani), has positioned himself as the de-facto leader of the transitional period. HTS has also announced a so-called Syrian National Dialogue Conference, aimed at uniting political and sectarian groups to address constitutional reforms aimed at drafting a constitution, but is yet to set a launch date.

The HTS-dominated transition period will be prolonged and take several years. The next government formation, expected to come in March when the term of the current interim government expires, will very likely remain dominated by HTS-affiliated figures. The group will seek to control key portfolios while promoting limited inclusivity by including a limited number of minority nominees, technocrats in particularly technical roles, and some other factions’ representatives. Meanwhile, Sharaa’s plan for drafting a new constitution spans three years, with national elections expected to be held within the next four years, contingent on the organisation of a national census.

New governance dynamics will likely emerge in Syria, balancing centralised authority with local autonomy. The Syrian state is likely to centralise key functions, such as security, finance and diplomacy, while preserving a degree of local autonomy. Key communal figures, including tribal and religious leaders who gained influence during the civil war, will likely retain their authority. This arrangement could be institutionalised through local representation mechanisms, such as employing local security forces and recognising traditional leadership roles. However, Sharaa has emphasised that Syria will avoid adopting a sectarian clientelist political model akin to Iraq or Lebanon.

The main challenge to state building that Sharaa will have to navigate over the coming months will likely involve navigating the demands of his conservative base with local and international demands for inclusivity and moderation. Although unlikely to adopt full democracy, the regime is likely to embrace limited inclusivity to gain international recognition and address concerns from segments outside HTS’s core constituency in Syria. At the same time, the HTS-led government will also cater to its conservative Islamist base, with the interim administration already taking steps such as revising the education curriculum and promoting foreign fighters to senior military positions.

Security challenges ahead

Alongside efforts to rebuild the new Syrian state and establish a new social contract within Syrian society, the HTS-led interim government’s primary objective will be to consolidate control over the legitimate use of force. A multitude of rebel groups operating outside state authority have emerged throughout the conflict. The interim government has begun establishing new security forces while working to disarm or integrate these groups into the new state’s security apparatus.

On 24 December 2024, Sharaa and several other opposition faction leaders agreed to merge their forces under the Ministry of Defence. However, SOR spokesperson Naseem Abu Orra told AFP on 8 January that the SOR opposes Sharaa’s plan to disarm and dissolve armed groups into the new Syrian army, insisting the SOR seeks integration as a “pre-organised entity” preserving its organisational structure.

Rebel groups in southern Syria, largely dormant since a 2018 reconciliation with the former regime and Russia, formed the SOR and aligned with HTS-led forces during the December 2024 advance toward Damascus. Strengthened by support from Jordan and the UAE, the SOR will likely resist HTS’s attempts to dissolve its forces into a centralised national army under HTS command.

An open conflict between the SOR and HTS remains unlikely, as both groups lack the motivation to trigger a new cycle of civil war and confrontation. HTS has more pressing security-related priorities, such as consolidating power in the areas under its control, particularly in former regime strongholds such as Latakia and Tartous governorates.

In this context, HTS will likely make concessions to groups resistant to full absorption into the new security forces. These concessions may allow such groups to retain operational autonomy while integrating into the broader Syrian security structure. Additionally, HTS is likely to permit these groups to continue managing their entrenched economic ventures in regions under their control.

Conflict risk in north

In northern Syria, tensions persist between the Turkish-backed SNA and the Kurdish-led and US-backed SDF. Türkiye continues to oppose Kurdish autonomy and exerts pressure on the SDF to disband or integrate into the new Syrian military structure. On 7 January, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan threatened military action if the SDF did not comply. In response, SDF Commander-in-Chief Mazloum Abdi announced on 9 January that the SDF came to an unspecified agreement with the HTS-led interim government to reject “any division projects”.

The SDF is currently negotiating the terms of its potential integration into the future Syrian armed forces with the HTS-led interim government. Still, it remains unclear if Türkiye would wait for these negotiations to conclude before launching an operation. The SDF may seek to integrate into the larger Syrian Defense Ministry apparatus by simply reflagging rather than fully dismantling its command structures. Türkiye is unlikely to be satisfied by such cosmetic changes.

For the SDF, the priority will continue to be avoiding a large-scale Turkish incursion while preserving its autonomous governance structures over its ethnic constituency. However, maintaining authority over Arab-majority areas and border areas with Türkiye will prove more challenging as pressure from Türkiye and the SNA increases. Turkish-backed SNA forces have mobilised near Manbij and Kobani. The US-brokered truce remains fragile, as both sides accuse each other of violations, and skirmishes continue along key flashpoints. These tensions and the threat of Turkish incursion will persist over the coming year.

Our outlook

The building of a new Syrian state under HTS leadership marks a critical juncture for the country’s future. HTS has consolidated its control, presenting itself as a pragmatic yet dominant force. Although aiming to centralise key state functions, the group is adopting a cautious approach that strives to balance the expectations of its conservative base with local and international demands for dialogue and inclusivity.

HTS’s efforts to integrate or disarm rebel groups underscore the challenges of consolidating military control in a country that has experienced a proliferation of armed factions since 2011. Although full integration into a centralised national army faces resistance, granting concessions to preserve the operational autonomy of certain groups will likely mitigate the risk of renewed conflict. The transitional period will likely be protracted, with constitutional reforms and national elections projected to take years.

Subscribe to our Middle East Monitor to stay updated on key developments and business impacts.