As the least climate-resilient region in the world, Africa needs to use this opportunity to mobilise crucial climate finance from developed nations.

This year’s COP (dubbed “Africa’s COP”) in Sharm el-Sheikh (Egypt) has been touted as a way for Africa to take a more central position in climate debates. Governments on the continent have always been present at and ratified the main climate agreements, including the 2016 Paris Agreement that set out emission targets intended to limit global temperature increases. For the most part, the implementation of these agreements in Africa means little on a continent which accounts for less than 4% of current global carbon dioxide emissions.

Several commitments were made at previous climate summits, including the recommitment by advanced economies to release USD 100bn annually to assist developing countries to build resilience to climate change. However, most sources agree that this goal has not been reached in recent years. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimated that member countries contributed USD 83.3bn in climate finance to developing countries in 2020. The World Bank said on 7 September that it had released USD 31.7bn in climate finance in 2022. The Climate Policy Initiative in June estimated that African countries alone require between USD 250 - 600bn annually between 2020 and 2030 to finance their plans to cut emissions and adapt to climate change.

But some academics and NGOs believe that the OECD numbers are inflated. For example, Oxfam estimates that the 2017-18 figures are closer to USD 19-25bn (than USD 71-78bn, respectively) arguing that, aside from grants, only loans offered below market interest rates should be counted. Meanwhile, there are ongoing debates about the “fairness” of climate finance obligations, with arguments that wealthy economies and the largest polluters, including the US, should pay greater amounts to finance climate change loss and damage.

Either way, African governments are expected to use COP27 to push Western governments to uphold their financing commitments for climate change response, adaptation and mitigation, as well as loss and damage, on the continent but will need quantifiable data in order to facilitate fruitful conversations.

The unanswered adaptation question

African countries have often borne the brunt of the impact of climate change, which is precipitating extreme changes in weather and climatic patterns. With a large population reliant on subsistence farming or pastoralism and cash-strapped governments, African populations are ill-equipped to handle the impending climate emergencies.

Adaptation programmes are rarely commercially successful. This is because they often entail providing direct financing to communities that are directly affected by the impact of climate change. In Africa, these are predominantly small-holder farmers and rural populations. While these have received increasing attention from impact investors – especially given the focus on food security – urban populations have often felt left behind. As a result, African governments and multilaterals such as the African Development Bank (AfDB) have increasingly called for greater investment in “green infrastructure” – infrastructure that considers climate change adaptation – to boost the resilience of African cities and populations to the increasing number of extreme weather events.

The proximity of major African cities such as Lagos (Nigeria), Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire), Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), and Cape Town and Durban (South Africa) to the coastline is exposing more populations to rising sea levels. Although governments are increasingly concerned about urban areas’ vulnerability to flooding, action has mainly been focused on emergency response rather than prevention. There is often limited capacity or financial resources at municipal levels to consider climate issues in planning. COP 27 will therefore be a useful platform to call for greater focus on adaptation issues, and financing at the regional and municipal levels, not just at the continental and country levels.

Finding this article useful?

Money matters

Regardless of who should pay what, African governments are keen to use COP 27 to ensure that they actually receive financing towards helping them meet their climate goals, although it will be very challenging for Western countries to honour commitments in the current inflationary environment with a looming global recession. Despite this we anticipate that governments will likely be successful in securing some commitments, likely to be focused on:

1. Loss and damage

"Loss and Damage" refers to costs already being incurred by countries from climate-related events or impacts. Vulnerable countries have long argued that developed countries should provide compensation due to their historical emissions. These have so far resisted the calls fearing spiralling costs. However, countries are hopeful that at COP27 discussions will be more fruitful and some sort of agreement will be reached.

2. Energy

Many African countries are rich in fossil fuels and have been advocating increase in their use as a step to develop their economies and provide electricity to millions who currently have no access to it. At the same time Europe has been trying to replace Russian gas imports with supplies from a range of countries and Africa has been seen a s potential source of alternative supplies.

At the same time the idea of global “decarbonisation partnerships” is likely to be a focal point for discussions, particularly for countries such as Nigeria and South Africa that are dependent on fossil fuels for most of their energy use.

Advanced economies may continue to finance renewable energy initiatives across the continent, given its high wind, solar and hydropower potential, and project developers will continue to find considerable opportunities in sub-sectors and sub-regions across the continent. Research commissioned by the International Finance Corporation in 2020 found that Africa has a technical wind potential of almost 180,000 terawatt hours (TWh) per year, enough to satisfy the entire continent’s electricity demand 250 times over. More recently, international oil and gas companies are themselves leading on renewable investments, as they too face pressure to cut their carbon emissions. These investments will help African countries expand access to power in a more sustainable manner. However, it the current Russia-Ukraine conflict has brought to life inherent contradictions in this agenda: European countries are looking for energy security and thereby currently increasing fossil fuel consumption. Many fossil fuel rich African countries are calling for further development and monetisation of their natural supplies as a means to progress social and economic development goals.

Africa’s green hydrogen potential will also likely be a focus of the conference. Namibia is already positioning itself to become a green hydrogen hub, having in recent months signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for a USD 9.4bn project with Germany that is anticipated to produce 300,000 tons of green hydrogen annually from 2026. South Africa is also looking to bank on green hydrogen projects, releasing its Hydrogen Roadmap in February to attract investment in the sector, particularly as it faces severe energy supply shortfalls. Under the roadmap, it intends to produce 550 kilo tons of green hydrogen by 2030. These governments are likely to use COP 27 as a platform to seek funding for these ambitious projects. For their part, advanced economies will be keen to engage with African governments on green hydrogen projects, especially as European governments look to pivot away from their reliance on Russian gas.

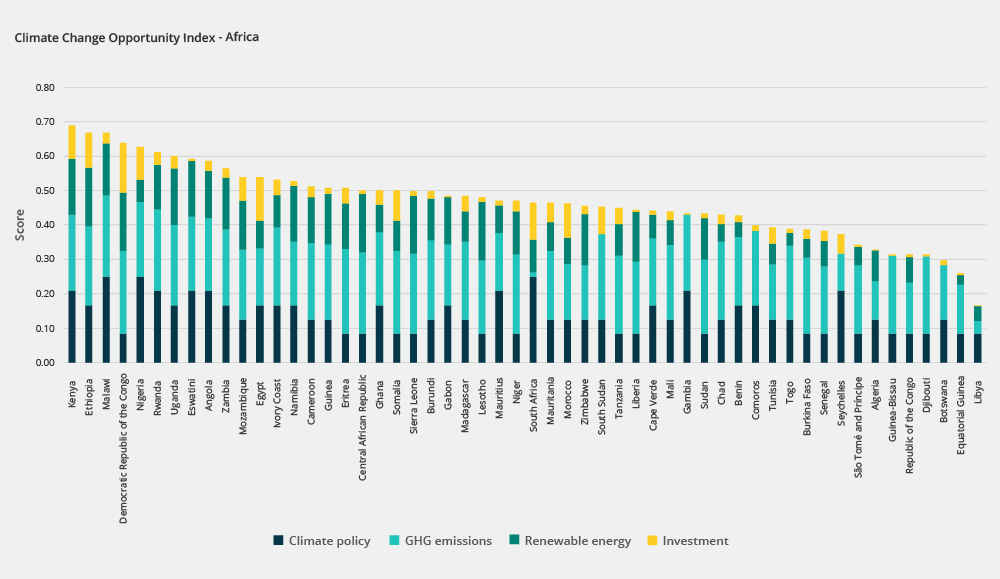

- Existence of climate change legislation

- Past reduction in GHG emissions

- Growth in renewable energy

- Climate change financing need

Kenya, Ethiopia and Malawi emerge as frontrunners due to their existing climate change legislation, relatively low emissions and modest number of renewables in the electricity mix, suggesting strong growth potential. This, coupled with the fact that we’ve seen them start to attract a fair amount of climate finance, means that these three countries are poised to reap the benefits of existing policies and climate action. On the other end of the spectrum, internal conflicts in Libya sees it suffer across all assessed criteria, scoring the North African country the lowest result.

African countries present significant market and investment potential for furthering green business entrepreneurship, eco-innovation and sustainable consumption and production. This data, coupled with legislative, financial, geopolitical and economic risk indicators for each country will feed into our proprietary Climate Change Opportunity Index (CCOI), due to be realised early 2023.

3. Food systems

Another key area of focus will be Africa’s food security. The issue has gained prominence in light of the disruption to global food supplies brought about first by the COVID-19 pandemic and then the conflict in Ukraine – both Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of grains and fertiliser. The IMF predicts that consumer prices in Africa will rise by over 12% in 2022 compared to 2021. Africa will import over USD 56bn worth of food in 2022, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). But Africa has always had pockets of food insecurity, given shifting climatic patterns and conflict in parts of the continent such as the Sahel and Horn of Africa. The COP 27 summit will likely be an avenue for African governments to seek funding for food systems projects, from boosting agricultural production to water management, and through to providing support to African countries seeking to boost their food exports to the rest of the world.

4. The critical minerals question

Meanwhile, one area of potential sensitivity at COP 27 and beyond is Africa’s role as a key source of critical minerals. Many of the technical components required to build green technologies including electric vehicles and batteries rely on copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earth minerals, many of which are found in African countries.

There is rising geopolitical competition for access to Africa’s critical minerals supplies. China has enjoyed first-mover advantages by forging strategic alliances with countries such as Congo (DRC) to have preferential access to such minerals. But others such as the US and the EU have increasingly sought to make similar deals. The US has explicitly identified critical minerals in its new US-Africa strategy, while the EU on 21 October reached a new deal with Namibia to secure access to rare earth minerals such as dysprosium and terbium needed in the production of batteries.

Given the comparatively lower levels of socioeconomic development in Africa, as other economies continue to develop and prosper from African resources, there has been a rising tide of resource nationalism among African governments to protect their access to such minerals. Although this has mostly been in rhetoric rather than policy or legislative developments, COP 27 will likely be used by African governments to highlight the disparities in progress towards a fossil fuels-free future which can be seen to only benefit advanced economies. This will likely increase negative scrutiny of companies involved along the entire industry’s supply chain for their impact, or lack thereof, on local communities.

How can Control Risks help?

Control Risks provides organisations with in-depth understanding of both physical and transitional climate change risks and helps organisations make more informed decisions to improve the resilience and effectiveness of their operations. Specifically, we can:

- Provide detailed country-by-country geopolitical and economic risk assessments, focusing on climate issues in the context of the country’s wider risk profile.

- Analyse current and future physical risks of climate change at national and site-specific levels to future-proof operations and assets.

- Analyse operational and supply chain risks by highlighting supply chain emissions and identifying emissions hotspots.

- Help project sponsors develop appropriate sustainability and monitoring frameworks to attract sustainable finance.

- Conduct ESG due diligence and gather intelligence on ESG risk factors for target investments, among a full suite of investment support.

This article is based on online analysis provided by Control Risks exclusively to Seerist. Find out more about Seerist – the only augmented analytics solution for risk and intelligence professionals.