Reasonable paranoia

Hikers and weekend backpackers read up and plan for allergies, bee stings and snake bites before heading to the hills. Governments regularly plan for disasters – relief agencies and emergency services receive billions of dollars a year and dedicate teams to gaming out terrible situations. Some have been warning about the impact of pandemics and climate change on business and infrastructure for many years.

And yet too often, we find that companies remain hesitant to think about the worst case.

A client called us recently for a meeting to discuss a risk assessment for her European tech firm in China. She started the meeting by saying, “We only want you to help us explore a worst-case scenario.” This was strange as clients typically like risk assessments to focus on best, most likely and worst-case scenarios. “We think we’re good with our best- and most likely-cases,” she said, “But the last few years have proven that worst-case scenarios seem to happen more often – a global pandemic, a land war in Europe, etc. We are not programmed to think negatively about our business. Given the state of the world, we think that we need to introduce some reasonable paranoia into our planning.”

This CEO was incredibly insightful. In today’s world, anticipating and planning for worst-case scenarios is critical to both building resilience and thriving.

In China, planning for the worst isn’t just about survival, it’s about finding a means to protect value generation in an increasingly challenging operating environment.

- Consumer brands in China need to think about being attacked in a wave of netizen inspired fury – often as a result of context associations or remarks. Companies that are able to anticipate these issues can earlier shape and head off online assault in the world’s largest online consumer market.

- Hi-tech manufacturers need to think about waking up to a new export control or trade restriction. They must ask themselves IF and for HOW LONG sales to China of critical components or doing business with their largest clients in the region can remain plausible. Preparing options for change, even if it involves downsizing, is critical for preserving market access amid increasing polarisation and localisation.

- Supply chains, hit hard by lockdowns in 2022 and outbreaks in early 2023, will face more bottlenecks and geopolitical constraints. Firms that have not fully mapped out how import or export controls by multiple players might directly or indirectly bring their business to a standstill are falling behind the curve.

How to plan for worst-case scenarios

Planning for worst-case scenarios is not only about considering the unexpected, but also about understanding an organisation’s key vulnerabilities that could pose existential risks. Building on most-likely scenarios, a limited set of adverse or worst-case scenarios can spotlight risk exposure or a lack of resilience for the business globally or in China, as well as helping to identify interdependencies.

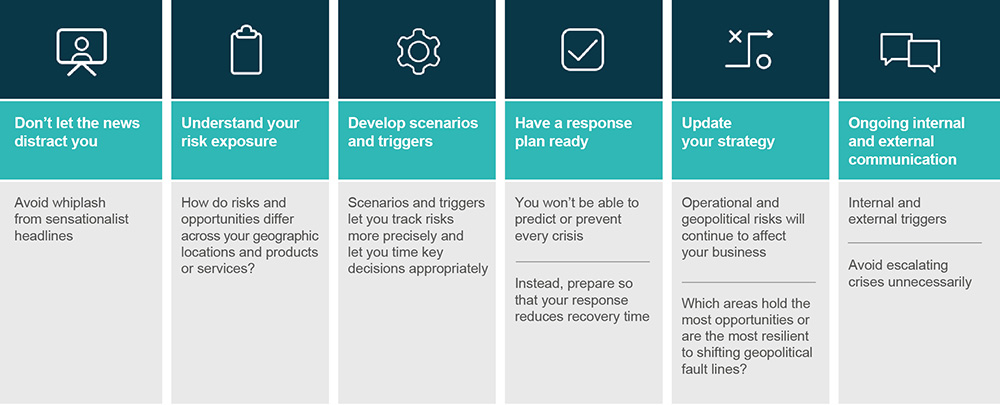

Worst-case scenario planning needs to be incorporated into a company’s overall risk management process (see example above). Rather than jumping to high-impact but unlikely end-states, companies should approach this type of scenario planning as a process, incorporating:

- Triggers and stages – there needs to be enough consideration of how we arrive at a predicted future. Triggers and related actions, and how escalation pathways might develop, need to be folded into scenarios, with commensurate actions and preparations for different stages.

- Specificity – planning often focuses on the internal, and fails to take full consideration of other actors and variables, especially third parties like suppliers, distributors and partners. Plans often fail to account for how situations affect the response of adjacent industries and actors.

- Operational, executable actions – planning often only arrives at generalised conclusions. “Find additional suppliers for critical input components” doesn’t really specify how different functions and roles should be responsible.

- Monitoring – plans and conclusions sit on the shelf, without being socialised across the organisation. Once a plan is set up, the responsibility for tracking triggers and important indicators then gets left to one side.

- Flexibility – be prepared to adjust and pivot in implementing response actions. The plan is a living document and needs to be updated along the way.

In 2023, China offers opportunities when downward economic pressures are affecting many companies in their home markets. Instead of being paralysed worrying about the wrong doomsday scenario, businesses should build resilience by examining more appropriate adverse scenarios.

In a global economy ripe with uncertainty, the only way to guarantee value for your organisation is to open your thinking on what could lie ahead – the good, the bad and the worst-case scenarios.