Russia’s trade with third countries means organisations need to adjust their approach to sanctions risk management

Countries that are not part of the Group of Seven (G7) or that are closely aligned with Russia find themselves along difficult geopolitical fault lines. The G7 sanctions against Russia have become an integral part of the bloc’s decoupling process from Russia. Resulting from the large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, 45 countries globally have imposed sanctions on Moscow. In this article, we will look at key third countries – specifically India, Kazakhstan and Turkey – that are of crucial importance in the debate over the implementation of sanctions against Russia, the reasons why these countries are important for the G7 sanctions regime, and their relationships with Russia.

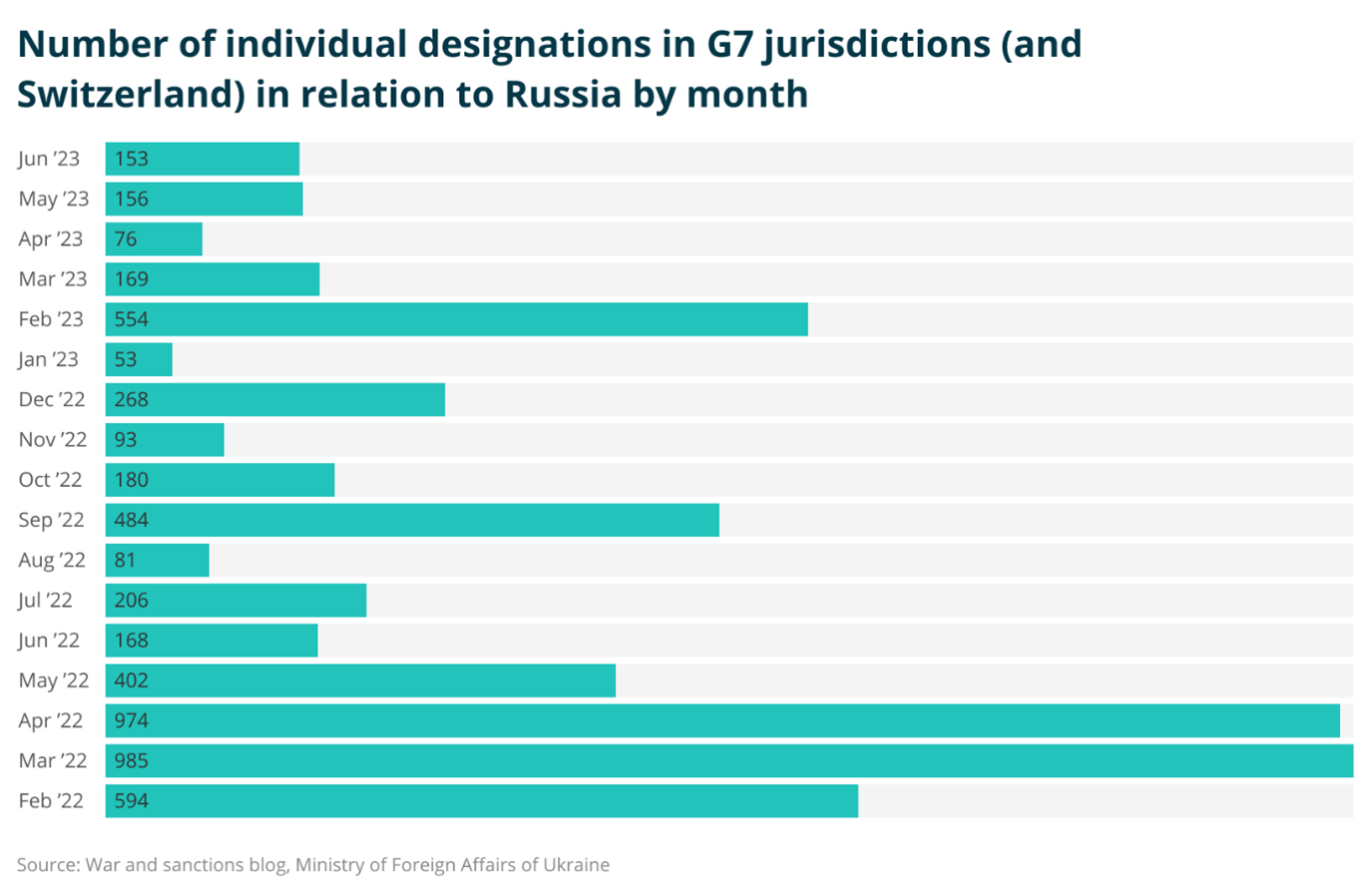

Despite broad agreement among G7 allies over the importance of these measures, it will become increasingly difficult for the bloc to agree on new Russian sanctions targets. The EU, member of the G7, fought for weeks over its 11th sanctions package (agreed in June 2023), shedding light on an increasingly heated debate within European capitals over sanctions politics. Meanwhile, our analysis, which is supported by media reporting and government statements, shows that sanctioned goods continue to flow into Russia via third countries. Moscow has ramped up circumvention tactics, with Russian trade volumes with dozens of countries increasing as a result of sanctions. In reaction to this trend, the US, UK and the EU have increased diplomatic pressure on third countries to enforce sanctions in their jurisdictions, including encouraging private sector companies to adopt more stringent sanctions controls and training.

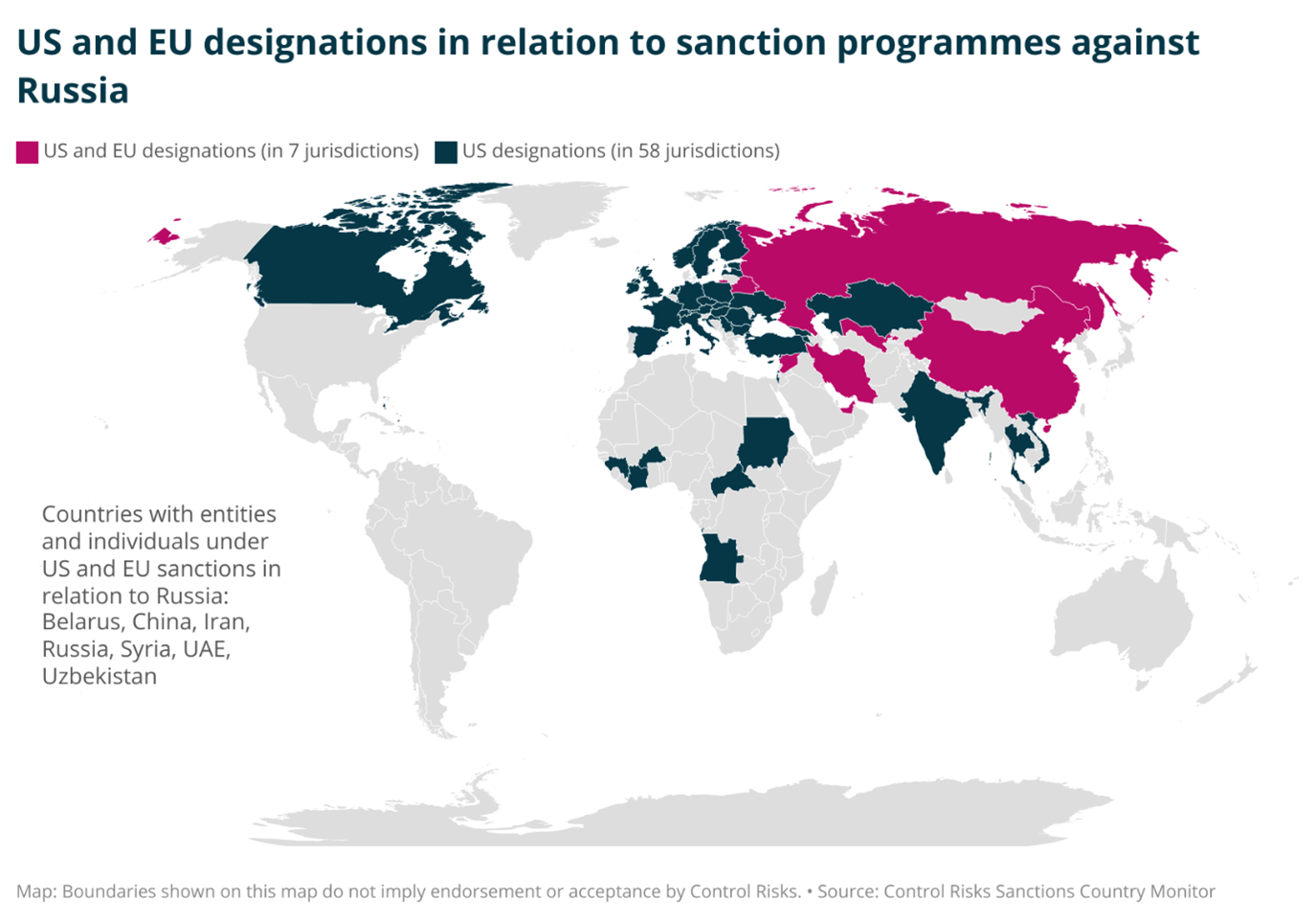

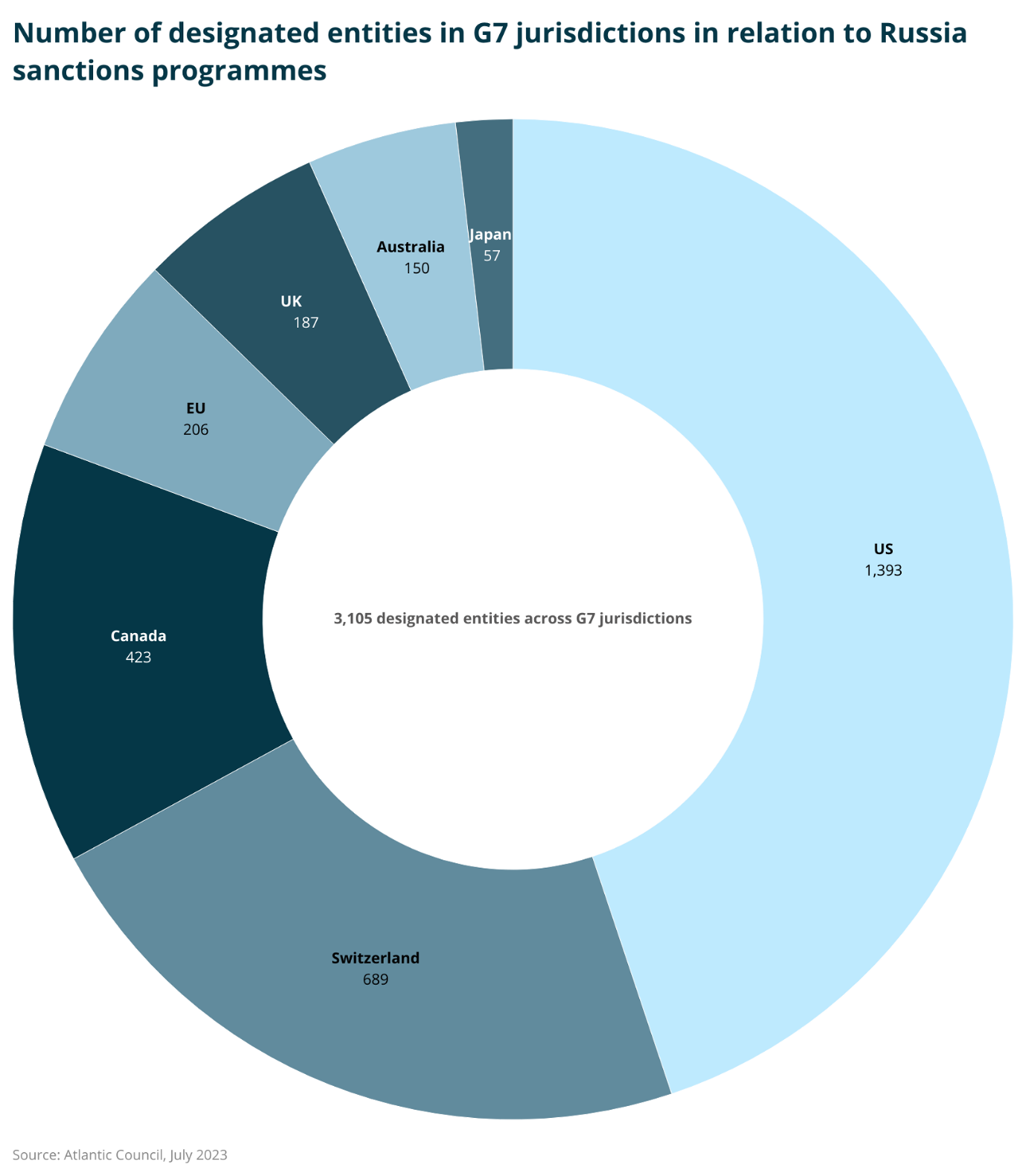

The US so far has designated entities and individuals in 58 jurisdictions globally in relation to its Russia sanctions programme. Under its new “anti-circumvention tool” (created as part of its 11th sanctions package), the EU imposed sanctions on entities registered in Iran, Hong Kong (China), Uzbekistan, the UAE, Syria and Armenia. All of these were designated for their alleged support in the circumvention of Russia sanctions. For the EU, imposing these sanctions on entities in third countries was a significant foreign policy shift. In the past, the bloc had opposed such third country sanctions by the US (especially under the Cuba and Iran sanctions programmes).

The expansion of sanctions on Russia and growing diplomatic pressure to comply with G7 sanctions have complicated relations with countries that are of vital importance for the G7 markets. Many of these third countries have close economic, political or security ties to Moscow and have not supported G7 sanctions against Russia.

India’s vital market

India is the most populous country in the world with more than 1.4bn people, has a large skilled manufacturing labour force, and is making a concerted effort towards developing into a powerhouse for space technologies. The country’s booming economy creates a growing thirst for energy resources and, since Russian oil imports were banned from G7 markets, India has taken advantage of discounted Russian oil imports. Russia has emerged as India’s most important oil supplier, and in June the country imported more oil from Russia than from Iraq and Saudi Arabia combined. Moscow also remains the most important defence equipment supplier for India, which faces longstanding tense relations with its neighbours Pakistan and China over border disputes.

The need to secure continued defence equipment supplies and fears of pushing Russia closer to India’s rivals Pakistan and China make New Delhi wary of alienating Russia over Ukraine. Consequently, India has not imposed sanctions against Russia over Ukraine and is unlikely to do so.

Indian businesses and individuals are unlikely to become primary targets for country- or sector-based G7 sanctions. Amid growing geopolitical tensions with China, both the US and India will seek a closer bilateral relationship in the coming years, and Washington is unlikely to be willing to jeopardise this relationship over Russia-related sanctions. For the EU, India is too important as an economic, security and geopolitical partner for Brussels to impose sanctions on India.

Nevertheless, the sanctions risks for companies in India is not zero. The US in May designated two India-registered entities and two nationals, accusing them of being part of a sanctions circumvention network that sold technology to Russian state-owned enterprises involved in nuclear weapons research and development. Any further US sanctions are likely to be highly targeted at certain companies or individuals and are unlikely to pose wider sanctions risks to other businesses.

We know based on our recent experience that Indian organisations have varying approaches to their relationships with Russia and Russian business partners, with organisations trying to grow their business interests while avoiding reputational and practical challenges related to sanctions. We have seen an uptick in due diligence requests from our clients on Indian counterparties with a focus on their exposure to Russian companies, either through beneficial ownership or the Indian company’s business relationships with Russia.

Turkey’s bargaining chips

Turkey controls vital global shipping routes via the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles straits, has used its NATO membership several times to veto critical decisions of the alliance and plays important military and political negotiating roles in conflicts in Libya, Syria and Ukraine.

Turkey’s trade with Russia has increased significantly over the past two years, and this as provided a welcome boost for the fragile Turkish economy. As a result of the G7 sanctions against Russia, Turkish logistics companies have come into high demand. Between March 2022 and March 2023, Ankara’s electronics exports to Moscow increased by 85%, according to the Atlantic Council. At the same time Russia is Turkey’s largest supplier of natural gas and Moscow is also heavily involved in the construction of Turkey’s first nuclear plant.

President Erdogan’s government has not imposed sanctions against Russia but, under pressure from the G7, Turkish state banks ditched the Mir payment system in September 2022. Turkey in March agreed to stop the transit of goods to Russia that are under G7 sanctions. Companies were handed a list of banned foreign goods and were instructed by the Turkish government not to transship these goods to Russia. Nevertheless, Turkey has not made further efforts to effectively enforce sanctions evasion in relation to Russia.

Despite various tensions and diplomatic disputes, the EU and the US are unlikely to impose sectoral or countrywide sanctions as the country remains a critical NATO member and a key interlocutor in Ukraine conflict. However, Ankara’s close economic relationship with Russia and existing sanctions programmes against Turkey mean that companies need to invest time and effort to mitigate the associated risks when investing or operating in Turkey. Over the past year, we have helped a number of clients that wanted to understand Russia-related sanctions risks as part of pre-investment or pre-partnership investigations in Turkey. The US in April designated Turkey-based entities and two related individuals for selling electronic technology to Russia.

Organisations with business interests in Turkey have experienced the challenges of sanctions circumvention in other contexts given Turkey’s trade relationships with Iran, Syria and other Middle Eastern economies, and Turkish subsidiaries – or agents and distributors – of multinational companies have conducted sanctioned trade that has led to their parent companies facing enforcement action. The lessons learned from these cases apply in the Russia context too. Pre-elationship due diligence and risk asssessments need to feed through to monitoring and auditing of business practices and transactions.

Kazakhstan’s resource shield

Kazakhstan’s uranium and oil wealth makes the country a key market amid growing geopolitical competition in the energy sector. The country produced 45% of the global uranium supply (fuelling nuclear power plants) in 2021. Eyeing Kazakhstan’s uranium wealth, Canada, France, Japan, the UK and the US on 16 April announced their intentions to diversify their nuclear supply chains to reduce reliance on Russia. Germany, Greece and France are all among the top five importers of Astana’s oil. Banning Russian oil from European markets has made Kazakh crude even more important.

Both dynamics have certainly set the scene for Kazakhstan to gain economic importance for G7 powers. At the same time, the conflict in Ukraine has cooled Astana’s relationship with Russia, and Kazakhstan has not recognised Moscow’s annexation of Ukrainian territory. Nevertheless, both countries maintain close economic ties and Astana has benefitted from increased trade flows as a result of Western decoupling from Russia. President Tokayev’s government has not imposed sanctions against Russia.

The US and the EU have both increased diplomatic pressure on Kazakhstan to enforce sanctions against Russia. The government publicly announced intentions to comply with G7 sanctions and has made some efforts to improve sanctions enforcement by tightening customs oversight. However, it is not endorsing sanctions. Fearing to upset critical export partners, Kazakhstan is unlikely to allow widespread sanctions evasion, and the country is unlikely to face US or EU country-wide sanctions. Nevertheless, the large amount of small and medium-sized businesses involved in trade with Russia will make it difficult for the government to enforce sanctions.

For companies operating in Kazakhstan or with Kazakhstani partners, sanctions risks remain regardless. The US imposed sanctions on several entities with touchpoints in Kazakhstan, and Washington is likely to impose further targeted sanctions against companies with ties to Russia’s defence sector, especially if the US finds evidence that companies aided Russia in breaching existing sanctions.

Our recommendations

The examples above demonstrate some of the challenges that Russia’s evolving trade relationships pose to organisations seeking to comply with G7 and EU sanctions against Russia. Governments have stated their political intent to address this trade through the extension and enforcement of sanctions. The likelihood of violating sanctions – whether intentional or accidental – and subsequent enforcement action is increasing and will continue to be elevated in numerous countries around the world.

Based on our experience advising organisations on sanctions compliance, when trading with or investing in countries with elevated exposure to Russia sanctions, we recommend:

- Monitoring changes in the risk profile of specific jurisdictions.

- Reviewing investigative reporting and advisories and enforcement action by governments to stay ahead of the product diversion tactics and trends that are relevant to your industry.

- Applying additional scrutiny to subsidiaries, third parties and end customers in countries trading with Russia by adjusting due diligence and risk assessment methods.

- Training frontline employees engaged in business development in the trends and tactics for product diversion and the legal consequences.

- Monitoring sales data in countries trading with Russia to identify anomalous sales activity.

- Conducting compliance audits of higher-risk subsidiaries and third parties to identify shortcomings in their approach to sanctions and product diversion, and monitoring the implementation of any improvements you mandate.

- Ensuring your whistle-blower hotline is open for internal and external use and that prompt action is taken to investigate any incoming reports related to any alleged breach of international sanctions.

Organisations that identify reasons to investigate whether product diversion has occurred have two broad means to do so: an internal investigation within their organisation and relevant third parties; or the use of external intelligence gathering into their business activity. The aim with both steps, which are not mutually exclusive, is to identify fact patterns and data points that support or refute that product diversion is happening, and in turn allow you to assess whether disclosures to government agencies are required.