A number of countries across the MENA region have turned to IMF bailout packages in recent years. However, political compulsions, insufficient institutional capabilities and capacity constraints will pose challenges to the ability of many of these countries to fulfil their IMF conditions – whether to secure financial assistance programmes or complete them. Failure to fulfil IMF conditions will hinder the countries’ economic recovery and growth prospects.

Companies operating or investing in the region should understand the degree to which these countries are successfully securing and complying with their IMF packages.

On course, off course

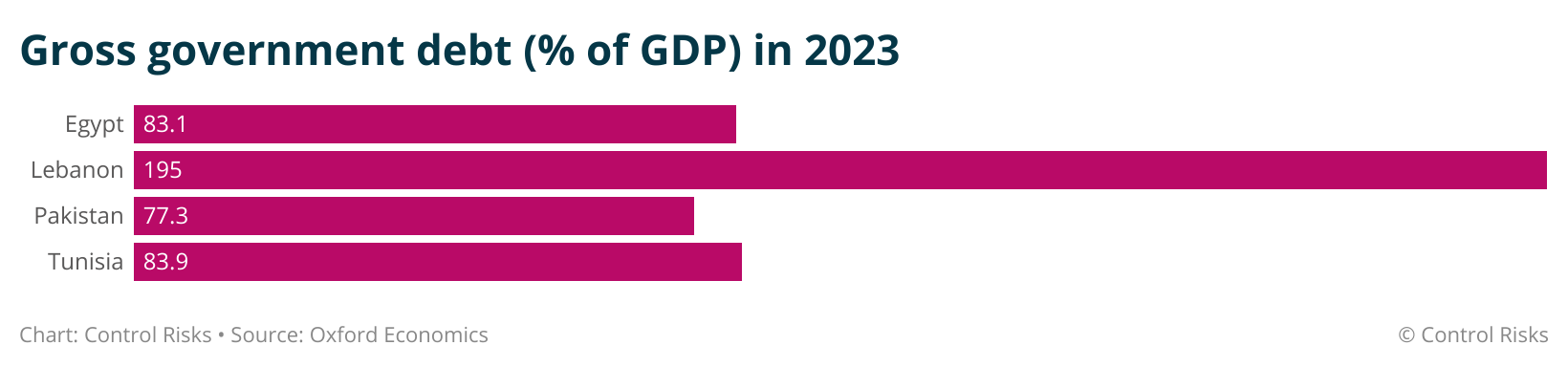

Persistent current account and fiscal deficits, elevated debt levels, structural inefficiencies and external shocks have all exacerbated economic and social pressures in low- and middle-income countries within the broader MENA region in recent years. This has driven some countries in the region—namely Egypt, Pakistan, Tunisia, Jordan, Morocco and Lebanon—to turn to the IMF for bailout packages.

Jordan and Morocco have stayed on course with their IMF programmes. The remaining four states are either poorly compliant with their IMF programmes or have failed to fulfil the conditions required to secure them.

Pakistan and Egypt have a particularly mixed track record of complying with the terms of IMF programmes. This has prevented both countries from completing scheduled reviews and/or securing additional packages in a timely manner.

Having begun a programme in December 2022, Egypt failed to complete its first and second reviews on schedule, not securing associated disbursements until March 2024.

Pakistan also experienced delays in its programme, only securing the package in late September after pursuing numerous measures, including rolling back tariff reliefs.

Tunisia and Lebanon have yet to secure IMF programmes. Both countries secured staff-level agreements in 2022, but a political vacuum in Lebanon and a lack of political will in Tunisia have prevented the countries from making concrete progress.

Hits on shorter timeframe reforms

To fulfil IMF requirements that require fiscal prudence and increased revenues, recipient countries will continue to pursue structural reforms with shorter implementation timeframes. These will include increased tariffs on energy, crackdowns on power theft (as in Pakistan), and subsidy cuts (as in Egypt).

However, amid economic pressure, recipient countries will likely seek to backtrack from IMF requirements or renegotiate reform implementation timelines to avoid causing popular discontent. Such efforts will likely hamper the complete and timely implementation of IMF programs, as the IMF will want to ensure the adoption of key aspects of its recommendations.

Misses on more permanent structural reforms

Governments will remain largely unwilling or incapable of undertaking longer-term structural reforms. They will continue to pursue cosmetic measures to portray themselves as adhering to IMF conditions, a strategy that will only sustain structural inefficiencies within their respective economies.

Domestic considerations will drive unwillingness as governments look to avoid ruffling stakeholders, from guarantors of political stability – like the military, in Egypt’s case – to key interest groups – like the real estate sector, in Pakistan’s case. In Tunisia, President Kais Saied’s reluctance and ultimate refusal to strictly comply with IMF requirements to cut down on government spending by reducing the size of state-owned entities after pushback from the country’s well-organised unions has prevented the country from securing an IMF programme. Saied will continue to rely on populist rhetoric for legitimacy while attempting to consolidate his power.

Despite the IMF’s continued emphasis in successive bailout packages on the need for Pakistan to widen its tax base, its government will likely avoid increasing taxes on untaxed or undertaxed sectors, such as real estate, associated with its support base. And even though concerns about political volatility and a weak economy have dampened investor sentiments, opposition from coalition partners – whose support remains essential to ensure government continuity – will slow efforts to privatise loss-making state-owned enterprises (SOE). Meanwhile, Egypt is unlikely to follow through on IMF conditions that require it to withdraw distortionary benefits for companies linked to the military amid President Abdul Fatah el-Sisi’s continued dependence on the military for support.

Persistent inefficiencies within states—poor coordination and insufficient capacity underpinned by bureaucratic red tape and corruption—will also hinder progress on structural reforms.

In Pakistan, even though the country’s latest Extended Fund Facility (EFF) package is the first time the programme has included provincial governments, tax revenues are unlikely to rise substantially due to capacity constraints. In Egypt, the authorities will aim to reform the country’s subsidy programme. However, plans to shift from blanket subsidies to a system of targeted financial transfers to vulnerable populations will likely fail to meet the stated July 2025 target due to insufficient information about the informal economy and the inability to reach the poorest segments of the population. Moreover, the increasing deprivation of the middle class will likely translate to mounting opposition to removing blanket subsidies.

Between a rock and a hard place

All in all, Egypt, Tunisia, Pakistan and Lebanon will be between a rock and hard place.

Tunisia’s postponement of the IMF’s planned visit to the country in December 2023 and Saied’s replacement of the former central bank governor Marouane Abbassi in February will undermine any negotiations with the lender – whose conditions include increasing the central bank's autonomy. The appointment of the new governor Fathi Zouhair Nouri – who aligns with Saied’s rhetoric – will undermine the central bank’s autonomy, and the president’s reluctance to pursue austerity measures will sustain delays in securing an EFF agreement, prolonging Tunisia’s weak economy.

In Lebanon, the political vacuum and an absence of institutional capability will continue to prevent the country from securing a programme with the IMF, and its economy will remain fragile.

Pakistan and Egypt will be in relatively better shape, given that they have already secured financial assistance programmes. However, further recovery will remain contingent on staying on course with their loan packages.

Companies with operations or investments in these countries should continue to monitor developments closely. For now, at least, there is no easy way out for the countries, while a range of factors complicate their ability to fulfil IMF conditions.