Conversely, the UK has no legislation in place to financially reward those who raise issues of concern, and is showing signs of a downward trend in the number of cases reported to regulators. What is behind this seemingly discouraging scenario in the UK? Is a lack of reward the key to understanding it?

Origins in the US

Congress in 2010 created the Securities Whistleblower Incentives and Protection Program through the provisions of Section 922 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) implemented this programme by issuing its Final Rules, which have been effective since August 2011.

In addition, other US regulators like the Internal Revenue Service and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission have their own whistleblower programmes, and the US Department of Justice (DOJ) routinely makes significant awards to whistleblowers in relation to prosecutions or other actions under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

UK perspective

In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) in 2015 introduced new rules regarding whistleblowing for banks, building societies and credit unions. No provision for payments to whistleblowers was included. Historically, the FCA had expressed its “concerns over the impact of incentivising whistleblowers financially”, stating that “financial incentives could create a number of moral and other hazards”.

The FCA rules addressed senior management accountability for whistleblowing, including requiring companies to have effective mechanisms in place for employees to raise concerns, as well as management responsibility for those mechanisms and for ensuring safeguards for individual employees.

As things stand, neither the FCA nor any other UK regulator – for example the Serious Fraud Office, the UK sister of the DOJ – offer financial rewards for blowing the whistle on poor corporate conduct, meaning that the decision to report is most likely to be driven by ethics.

The figures

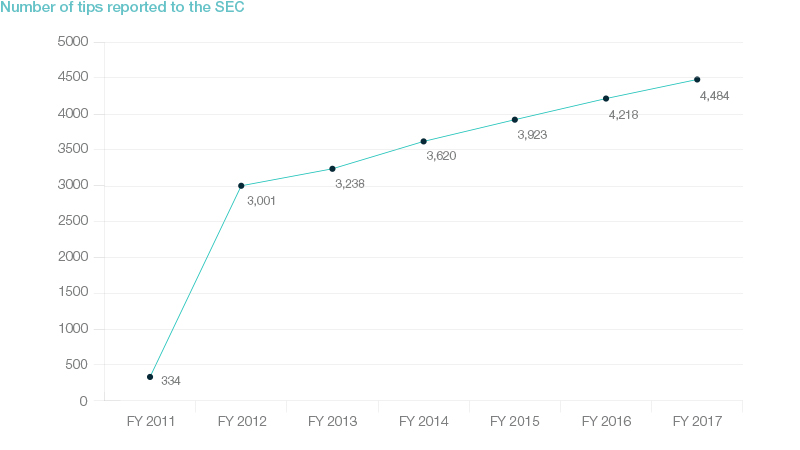

The FCA suggested in its 2014 statement that no US agencies had shown a significant increase in the number of whistleblower reports since the advent of financial incentives. However, that is definitely not the case for the SEC, which (according to the latest report issued for the fiscal year ending on 30 September 2017) has received more than 22,000 whistleblower reports since August 2011.

To date, the SEC has awarded more than USD 250m to whistleblowers whose reporting led to a successful enforcement action. In March 2018, two whistleblowers shared a reward of nearly USD 50m and a third whistleblower received more than USD 33m. Enforcement actions from whistleblower tips have resulted in more than USD 1bn in financial remedies.

Across the pond, however, annual whistleblowing levels are showing signs of a downward trend. Prior to the UK’s Financial Services Authority splitting into two separate regulators, the number of reported whistleblowing cases was somewhat underwhelming, though in financial years 2013/14 and 2014/15 there were signs of growth. Nevertheless, the past two financial years show a decrease, and it will be interesting to see where this trend goes once the FCA releases its figures for 2017/18, expected around July.

The other side of the story – the Barclays scandal

Is it as simple as money talking, or are there other issues at play?

Lord Cromwell (co-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Fair Business Banking and former vice-president of Barclays Wealth) recently stated that whistleblowers in the UK banking industry were being gagged, and risked persecution and unemployment. He suggested adopting the US system of financial compensation to protect them from financial hardship.

Lord Cromwell cited the recent example of Barclays’ board receiving anonymous letters raising concerns about the recruitment of a senior employee and his reputation. CEO James “Jes” Staley was fined GBP 640,000 (his salary was GBP 3.65m) by regulators. He was also allowed to keep his CEO position by Barclays, despite using the bank’s internal security unit to try to identify the author of the letters and despite the FCA rules on protection of whistleblowers.

The general perception in the UK is that there is limited reward for blowing the whistle, even removing the lack of financial incentive from the equation. Time and time again, in investigations that I have undertaken, I have seen the whistleblower negatively impacted, often feeling ostracised from colleagues and – rightly or wrongly – concerned for their anonymity. The Barclays decision is likely to exacerbate that view.

The effectiveness of the UK’s system, therefore, remains under scrutiny in light of these potential trust issues, the risks taken by the whistleblowers, and the lack of financial motive to turn to the relevant regulators to tackle suspected transgressions. At present, it is understandable that whistleblowers may not feel as protected as they should be.

So, how can we help paint a better picture?

UK plc has to fully embrace whistleblowing policies as tools to build trust and credibility with employees and external stakeholders if companies are truly committed to ensuring a robust ethical reputation.

Investing the appropriate resources in clear and fluent communication of the scheme and training employees on how to use it will help ensure its success and create an embedded culture that strongly encourages, values and protects those who raise matters of concern. That is step one. Step two is to fully adhere to correct procedures when reports are received and to make all possible efforts to protect the anonymity of the whistleblower.

As for financial rewards, I personally can only see benefits emerging if they encourage witnesses of unethical corporate conduct to come forward to hold our companies and their management accountable for their behaviour. A regulatory shake-up would send the right message to the business community and society as a whole: “doing the right thing is rewarded, doing the wrong thing is punished”.

Author

- Maximiliano Barrios, Senior Consultant