Despite three consecutive annual falls in investment inflows and a continuing debt crisis, Mozambique remains one of Africa’s top FDI destinations. FDI inflows were USD 3.4bn in 2016, according to the African Development Bank, testament to the continued potential that investors see in the country. This was directed to more diverse sectors than might be expected ahead of an anticipated natural gas boom, with investment flowing into transport and logistics, real estate, and coal.

The financial, real estate, telecommunications and tourism sectors in particular have enormous potential that could be developed as Mozambique’s economic situation improves. Investors who discount these other economic sectors risk overlooking substantial opportunities.

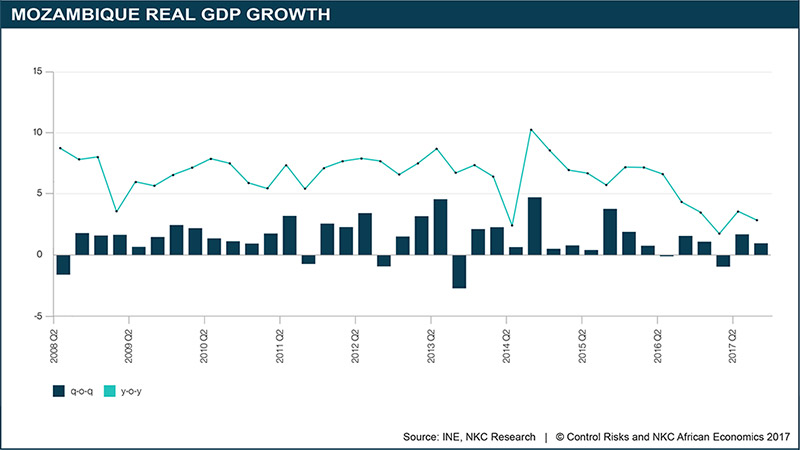

A myriad of economic headwinds has eroded the country’s economic growth in 2016, when real GDP growth fell to 3.8%, the lowest growth rate since 2000. While the Mozambican economy once again posted a relatively weak performance during the first and second quarter, this was not unforeseen, given the ongoing spill-over effects from the external debt scandals. The finalisation of negotiations with gas operators will unlock investment in major extractive projects and infrastructure that will drive growth from 2018 onwards. Our economic growth forecast over the medium term remains above 5% per annum, although this forecast is subject to significant downside risks.

These opportunities have long existed. Mozambique has always had huge latent potential arising from its mineral wealth; its geographical position as a gateway to the landlocked markets of Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi and eastern Congo (DRC); and its relatively untapped domestic market. But three main factors mean that these opportunities are now looking increasingly attractive.

First, the economic growth likely to be driven by the extractive sector will have a spill-over effect. New-found wealth will create a market for a range of goods and services that were previously out of reach for all but a handful of local consumers, and infrastructure improvements required by extractive industry mega-projects can be used by other industries to access these markets.

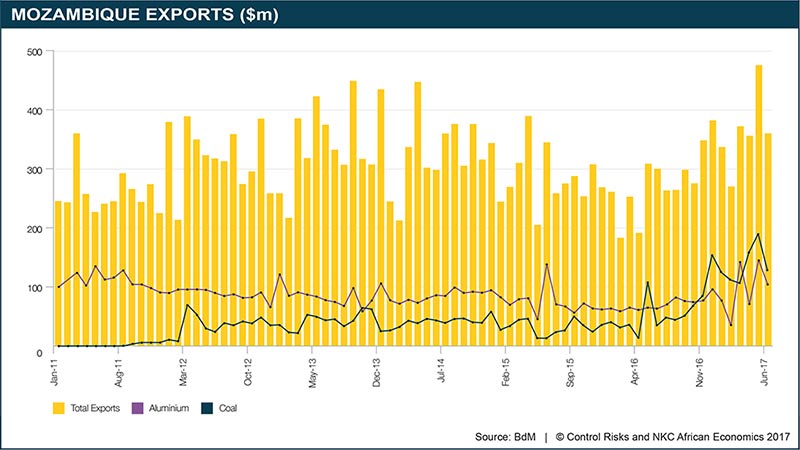

The metical bounced back and stabilised around the MT60/USD level since mid-May, whilst the trade deficit narrowed substantially as exports increased on the back of a rebound in aluminium and coal prices. Mozambique’s current account deficit is set to narrow this year due to higher exports on the back of higher aluminium and coal prices. Next year, an increase in exports will be offset by a large investment-related import bill. Mozambique’s large current account deficit is less worrying when one considers the substantial amount of foreign direct investment (FDI) related to the gas industry that the country is set to receive.

Secondly, a shift in the government’s economic policy is opening up the playing field to new entrants. The suspension of budget support by donors following the April 2016 revelations of illegally obtained debt accumulated by state-owned companies has left the government facing severe budgetary constraints. In response, it is taking steps to reduce the state’s role in the economy. Frequently loss-making state-owned companies are being privatised or restructured to reduce liabilities, assets sold to raise capital and previous monopolies opened up to FDI.

Finally, and combined with this shrinking state role, legislation and regulations are changing to attract FDI. The cash-strapped government is increasingly looking to the private sector to drive development and replace donor assistance; companies that arrive with ideas and resources will be warmly welcomed.

Relying on the private sector

The government has grand plans. A host of long-term strategy documents, such as the Agenda 2025 and National Development Plan 2015-35, put forward goals such as achieving middle-income status by 2025 (albeit with vague suggestions as to how to achieve these). And while the government is eager for natural gas to fuel an economic boom, these documents demonstrate high hopes for sectors and subsectors ranging from fisheries to telecommunications. In the 11th Congress of the ruling Frelimo party, scheduled to be held between 26 September and 1 October, a five-year party programme that identifies infrastructure, energy and tourism as ‘pillars to support inclusive and sustainable economic growth’ will be approved.

However, a massive gap exists between the government’s ambitions and its fiscal resources. The shortfall in government capacity is arguably nowhere more evident than in the area of transport infrastructure. Minister of Transport and Communications Carlos Mesquita said that USD 13.8bn would have to be spent on the construction and maintenance of railways, roads, bridges and airports. In reality, the 2016 budget allocated less than USD 700m to infrastructure, an amount that has increased only slightly in 2017. Yet the grandiose ideas continue unconstrained by budget realities: plans to build a 3,800km railway connecting the north and south of the country at an estimated cost of USD 20bn were unveiled in June.

To cover this shortfall, the government is relying on the private sector. It is increasingly looking to public-private partnerships (PPPs) and concession models to fund infrastructure developments, often on generous terms to attract investor interest. While such models transfer a degree of risk to investors, they also allow for companies to identify and develop opportunities beyond the government’s somewhat ill-defined – and often politically motivated – priorities. Indeed, companies are increasingly choosing to put forward unsolicited proposals for infrastructure projects rather than compete for government contracts in tendering processes that are widely regarded as corrupt (although unsolicited proposals must legally still be put to a public tender, a lack of detailed regulations means that the proposing company is often granted the ensuing contract). Some of Mozambique’s largest infrastructure developments are the result of private-sector initiatives eagerly facilitated by the government.

Similar dynamics are at play when it comes to energy infrastructure. The potential for huge expansion of electricity generation and transmission is clear. Only between 20% and 35% of the population currently has access to electricity, energy-intensive industries are growing, and Mozambique’s neighbours – in particular Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe – would welcome external additions to their own constrained energy supplies. Mozambique currently obtains the overwhelming majority of its power from the Cahora Bassa hydroelectric facility, leaving most of its coal, natural gas, wind and solar potential untapped.

State power utility Electricidade de Moçambique (EDM) on 14 August announced plans to invest USD 16bn by 2030 to expand the grid, as part of a longer-term goal of achieving universal access to electricity across Mozambique. A number of new generation facilities are already planned or under construction. To achieve these ambitions the government is again turning to the private sector. Since the first independent power producer (IPP) projects came online in 2015, the model has become widespread and standardised. Many of the new power projects are now being developed by private companies, especially in Tete province, where coal-fired plants are often linked to mining developments. Power projects have also attracted significant interest from international donors, particularly as they look to replace suspended direct budgetary support with project-specific funding.

Reducing competition, removing restrictions

President Filipe Nyusi in December 2016 announced that the government was in the process of selling or dissolving 64 of Mozambique’s 109 state-owned enterprises, and restructuring the remaining 45. The Institute for the Management of State Holdings (IGEPE) had previously stated that it planned to sell or close 40 state-owned enterprises by the end of 2017. For the government, this significant reform of the state’s role in the economy is motivated by its fiscal challenges. For investors, it represents an opportunity to make a mark in sectors where state-owned companies previously posed tough – and sometimes unfair – competition.

The scaling back of pervasive state interests will change the commercial landscape in a number of sectors. Increased use of IPPs is slowly diluting the monopoly of EDM. Meanwhile, Caminhos de Ferro de Moçambique (CFM), the parastatal that oversees the country’s railways and connected ports, was once accused of pushing for a private-sector partner’s concession to be terminated so that it could take over its operations. It is now selling assets and reining in its ambitions. The first public tender to allocate domestic, regional and inter-continental flight routes was launched in April, breaking the domestic monopoly held by national airline Linhas Aéreas de Moçambique. In telecommunications, the merger in June of state-owned fixed-line operator Telecomunicações de Moçambique (TDM) and state-owned mobile (cellular) operator Moçambique Celular (MCEL) is part of a continued restructuring, as both adjust to a more competitive market. Dominant state-owned logistics players such as Silos e Terminal Graneleiro da Matola (grain storage and transport) and Aeroportos de Moçambique (airport management) are being restructured and their mandates reduced.

As state-owned companies start to withdraw from various sectors, legislative and regulatory changes are being made to encourage private-sector investors to take their place. In some cases these changes are relatively minor and designed to promote growth in already attractive sectors. A number of initiatives – such as the introduction of visas on arrival in April – have been taken to promote the tourism sector. Other changes are more significant. The Telecommunications Law of 2016 simplified and improved the regulatory environment for telecommunications operators, lowering barriers to entry. And a few have opened up sectors that were completely closed to foreign participation. For example, a cabinet decree in August 2016 granted foreign ships registered in Mozambique the same treatment and access to facilities as Mozambican ships in a bid to boost cabotage, a promising sector in a country where 60% of the population live within striking distance of a 2,500km coastline.

Fulfilling Mozambique’s potential

Even as these opportunities become increasingly attractive and accessible, challenges remain. The government’s drive towards greater liberalisation was reportedly urged by local businesspeople, who are likely to lean heavily on political connections to ensure that they benefit from the result opportunities. Foreign entrants will face tough – and sometimes unfair – competition, while those partnering with local players risk getting entangled in complex political webs.

Moreover, all sectors in Mozambique rely to some degree on coal and gas proceeding without disruption. Outside Maputo, Mozambique remains poor and sparsely populated. Without extractive industry mega-projects to drive economic growth and infrastructure construction, the cost of reaching a population located in small remote rural communities can be prohibitive. But Mozambique made huge strides towards a gas boom when it finalised a deal with Italian energy company Eni in June, and coal projects are finally overcoming the challenges that tempered initial excitement in the sector.

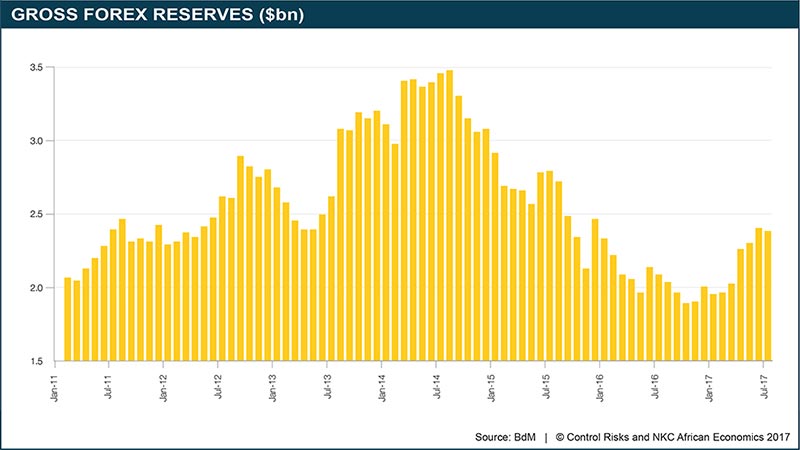

Overall, Mozambique’s economic outlook remains positive, and gradual improvements in the country’s macroeconomic situation have been driven by non-hydrocarbon sectors. The metical bounced back and stabilised at around 60 to the dollar since mid-May, while the trade deficit narrowed substantially as exports increased on the back of a rebound in aluminium and coal prices. The current account deficit is set to narrow further this year in light of higher exports of aluminium and coal. Foreign exchange reserves have started to rise after three years of decline, and the central bank’s forecast shows a continued downward trend in inflation, to reach 12.2% year-on-year by the end of 2017.

After reaching a peak of almost $3.5bn in August 2014, Mozambique’s gross foreign reserves started to trend down, falling to some $2.4bn by the end of 2015 and to barely $2.02bn at end-2016. This sharp reduction in reserves was largely due to the struggling metical: the central bank had to intervene in the foreign exchange market in order to stem the local unit’s slide. Other issues which exacerbated these difficulties were lower FDI inflows related to mega-projects and weaker export growth in 2016, particularly in the coal industry. In 2017 the trend has been positive: reserves have increased from under $2.0bn in January to $2.4bn by end-July, a sign of healthier export revenues thanks to higher coal and aluminium prices on global markets.

Investors should not ignore the challenges that come with working in Mozambique, some of which will be discussed in further articles in this series. But it would also be a mistake to ignore the substantial opportunities, or to believe that these opportunities are concentrated solely around the extractive industries. Mozambique is at the start of what is likely to be a rapid period of development, and recognises that it needs private-sector help to drive this forward. Those companies with the ability to contribute will find it a very welcoming place.