The “Free Senegal” protests that swept the country in March undermined its reputation as a stable democracy, and ended an era in which the ruling coalition experienced little pushback against its political agenda. We consider the challenges that now lie ahead for President Macky Sall.

- The protests have redrawn the political map. The ruling Benno Bokk Yakaar (BBY) coalition’s political future looks more uncertain, while the opposition has been strengthened ahead of the 2022 legislative elections.

- Running for a third term in 2024 will now seem a more politically difficult option for Sall, though he will hold off deciding whether to stand pending the outcome of the legislative polls.

- Although the government will retain its pro-business stance and continue to carve out opportunities for foreign investors, operators will likely come under greater scrutiny in the coming years, particularly as the oil and gas sector develops.

- Despite growing tensions, broad political stability is not under threat. Nonetheless, the coming years will be turbulent, with political and socioeconomic grievances fuelling periodic unrest.

Fading star?

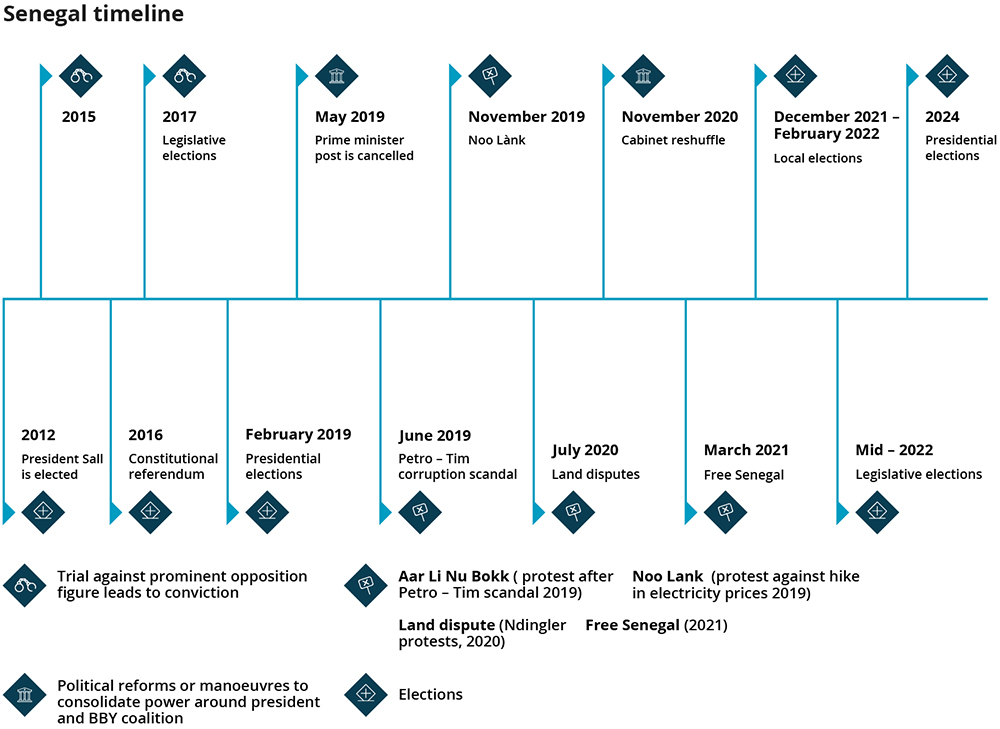

Senegal in recent decades has built a reputation as a stable democracy in a region marred by flawed elections, civil wars and military coups, conducting peaceful transfers of power in 2000 and 2012. However, since Sall decided to stand for re-election at the February 2019 presidential poll, political competition has crumbled as BBY’s dominance of the National Assembly (legislature) and the abolition in 2019 of the role of prime minister have consolidated power in the hands of the president. In 2021, NGO Freedom House rated Senegal as only “partly free” for the second year in a row, having initially downgraded it as a result of Sall’s comfortable re-election in a race where his two strongest opponents had been barred from running.

Democracy weakened

In the last five years, Senegal’s democratic model has morphed into the type of dominant-party system seen elsewhere in West Africa. The opposition has been hollowed out, and checks and balances on executive power eroded. In late 2020, BBY further cemented its political dominance when Idrissa Seck of the opposition REWMI – Sall’s main rival at the 2019 presidential election – joined the government, underlining BBY’s successful absorption of high-ranking opposition figures. Since the 2012 presidential election, historically prominent parties such as the Socialist Party (PS) and Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS) have gradually been pushed to the political margins.

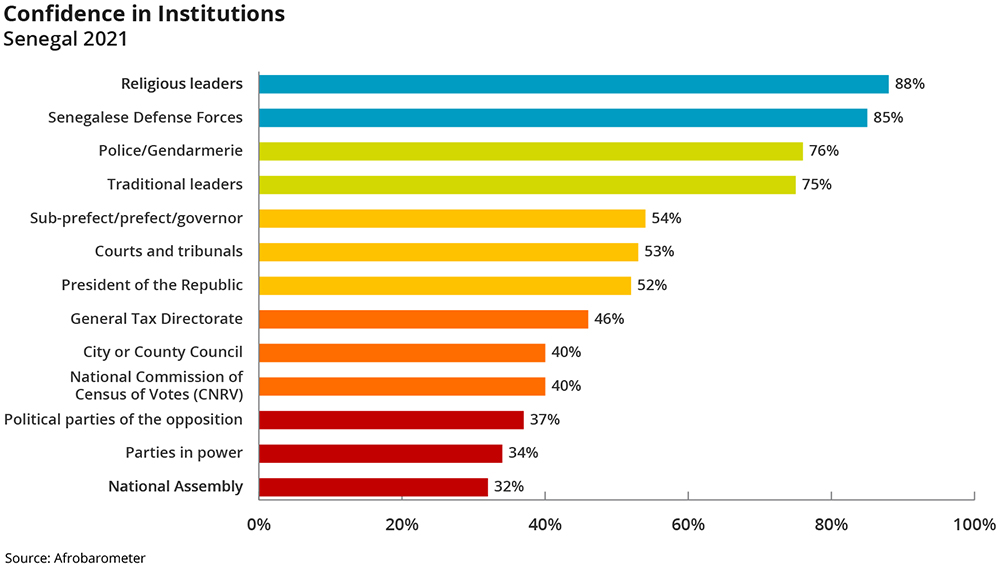

Meanwhile, political interference in the judicial branch is also contributing to a gradual deterioration in political rights and civil liberties. Despite being a stable electoral democracy, the rule of law has historically been weak. Civil society groups have been the most vocal source of dissent, condemning the erosion of the public space under Sall. The arbitrary arrest of political activists on dubious grounds such as inciting disorder or outrage against the head of state, and attempts to muzzle journalists have led to tensions at the highest level of the judicial branch. In October 2020, a progressive judge received a warning for openly criticising a court ruling, underlining unease over the influence of the executive on key institutions. Prominent figures close to Sall’s inner circle have walked away from corruption allegations, while opponents – including former mayor of Dakar Khalifa Sall and Karim Wade – have been jailed. This trend has consolidated perceptions that investigations against opponents are ultimately part of a political witch-hunt.

It was in this tense context that rape accusations levied in early February against Ousmane Sonko, leader of the opposition Patriotes of Senegal (PASTEF), rapidly became politicised, triggering unrest on a scale not seen in Senegal since 2011. This can be partly attributed to Sonko’s growing popularity among student unions and youths in peripheral areas of the capital Dakar, with demonstrations beginning at the University of Dakar. However, it was the government’s miscalculations about its own popularity and ability to weather the Sonko storm amid a tense economic climate and ongoing COVID-19 restrictions that set the capital ablaze.

Sonko’s arrest inevitably spiralled into a wider confrontation over issues of social justice. Grievances over rising living costs have been at play in Senegal for many years. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated them and caused irreparable damage to public perceptions of the government. The consolidation of power around Sall has perpetuated the view that the main beneficiaries of government actions are his inner circle and support base, a narrative Sonko has championed in opposition. A survey by regional research network Afrobarometer published in March showed that while 65% of respondents believed that the government’s response to the pandemic has been effective, 68% think it has involved some level of corruption, while 40% believed that access to government assistance had been “very inequitable”.

End of an era

Although the Free Senegal protests have petered out, their impact will continue to reverberate. The unrest marked the end of an era in which BBY had consolidated its political powers without facing a significant popular backlash. Weakened by the protests, the ruling coalition’s political future now looks more uncertain.

The next key political milestone is legislative elections set for mid-2022. BBY has already started campaigning. Securing a majority in the National Assembly – which serves a five-year term – would enable it to keep one foot in government regardless of the outcome of the 2024 presidential election.

However, the protests have revived a sense of unity among the political opposition. New opposition parties, some of which have splintered from the PS and PDS, are stepping up to fill the void left by the collapse of traditional opposition forces. Although his political future remains uncertain, Khalifa Sall of Taxawu Senegal is pushing for the opposition to unite ahead of the polls. An alliance between Khalifa, Sonko and Barthelemy Dias, the popular mayor of Mermoz-Sacré Coeur in Dakar and a former member of the PS, is expected to lead a unified list, preparing the ground for an electoral battle. They are also likely to seek the endorsement of other opposition parties in the coming months, and could be joined by some former ministers, strengthening their chances in key electoral battlegrounds.

The legislative elections are thus likely to herald an upset for BBY, with the opposition likely to prevent the ruling coalition from winning another majority in the National Assembly. We expect the opposition to retain the city of Dakar – its stronghold – while winning several seats in rural areas previously held by BBY. This will put it in a strong position ahead of the 2024 presidential elections.

Call to action

Despite speculation that Sall intends to run for a third term in 2024, he is unlikely to make a final decision until after the 2022 legislative elections. His ability to restore popular support, secure control of the legislature and bring about a rapid economic recovery will be key to his decision-making. After the recent protests, a third term will likely appear increasingly difficult to achieve without a popular backlash, while the outcome of the election itself has become even more uncertain.

Transformation derailed

Before the pandemic, the government’s Emerging Senegal Plan (PSE) development plan had translated into strong economic growth. However, its focus on major infrastructure projects has failed to create jobs and opportunities for young people. A resurgence of irregular migration in August-October 2020 underlined the growing lack of prospects for youths and the dire economic situation in coastal fishing communities. As key industries such as tourism continue to suffer from the global economic downturn, the government will inject more funds into bailouts and social relief packages. On 3 April, Sall announced an XOF 80bn (around USD 147m) plan to support the recruitment of 65,000 youths into public-sector jobs in various sectors.

Overall, the business environment will remain favourable, with new opportunities for private sector investors. The protests will not disrupt deal-making or alter the government’s pro-investment approach. In February, the National Assembly passed a new law on public-private partnerships (PPP), strengthening the legal framework for local and foreign investors to actively participate in the second phase of the PSE in the coming years. The government has just secured XOF 1,024bn (USD 1.9bn) in financial commitments from bilateral and financial partners to support its bid for universal electrification by 2025.

However, as the government refocuses its attention on addressing youth grievances, it will increasingly look for vote-winning social initiatives, likely affecting the timing and prioritisation of some investment projects. The General Delegation for Rapid Entrepreneurship (DER) will be at the heart of this strategy – the government has confirmed financial commitments of more than XOF 450bn (around US 829m) for young entrepreneurs over the next three years.

Investing in Senegal

The energy sector – where Sall has achieved most success – will attract most scrutiny in the coming years. Oil and gas companies have until the end of May to submit bids for the country’s first-ever oil licensing round. New contracts are guaranteed scrutiny from civil society groups, and any allegations that some bidders received preferential treatment could further taint the government’s reputation.

Meanwhile, oil and gas projects already underway will become more visible from mid-2021 when drilling on the first oil project is scheduled to start, driving rising scrutiny from civil society and opposition groups and testing the resilience of community relations. Concerns about labour conditions and environmental risk are likely to occupy more space in public debate given Senegal’s fragile coastal ecosystem and artisanal fishing economy.

Scrutiny will extend beyond the oil and gas sector. Infrastructure and real estate developers perceived as having received preferential treatment in the allocation of contracts and land deeds will also be exposed to reputational risks.

Existing investors have generally enjoyed positive relations with the Sall administration, and continue to see Senegal as a peaceful, welcoming destination. However, shifts in public opinion could also expose them to blowback, either for being perceived as too closely aligned with Sall or for threatening local jobs. For French operators, the March unrest demonstrated that this risk can translate into hostility and potential material damage, with supermarket chain Auchan and fuel stations operated by Total targeted during protests.

Outlook

Nonetheless, despite a likely rise in tensions and uncertainty in the coming years, broad political stability will be maintained. Interventions by influential religious leaders to moderate between opposing interest groups highlight the continued strength of moderate forces in Senegalese society. Nonetheless, the coming years will bring increased turbulence – and further outbreaks of unrest – as the next electoral cycle unfolds.