Israel has started administering COVID-19 vaccines to demographics that present lower health risks, including teenagers and individuals over 40 years old. Meanwhile, ten states across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) are yet to receive their first shipment of vaccine doses.

- As Israel and the UAE vaccinate at breakneck speed, they will likely further ease COVID-19-related restrictions in the coming months.

- Most MENA countries will be unable to follow Israel and the UAE, both of which benefit from their wealth, well-developed healthcare infrastructure and comparatively small populations across small territories.

- States with insufficient healthcare infrastructure – including Iraq, Egypt, Lebanon and Iran – and conflict zones – such as Libya, Syria and Yemen – will continue to be affected by the COVID-19 pandemic throughout 2021.

- Vaccine diplomacy will become more prevalent in the second half of 2021, as China and Russia will seek to build political capital in MENA by supporting vaccination campaigns.

The haves…

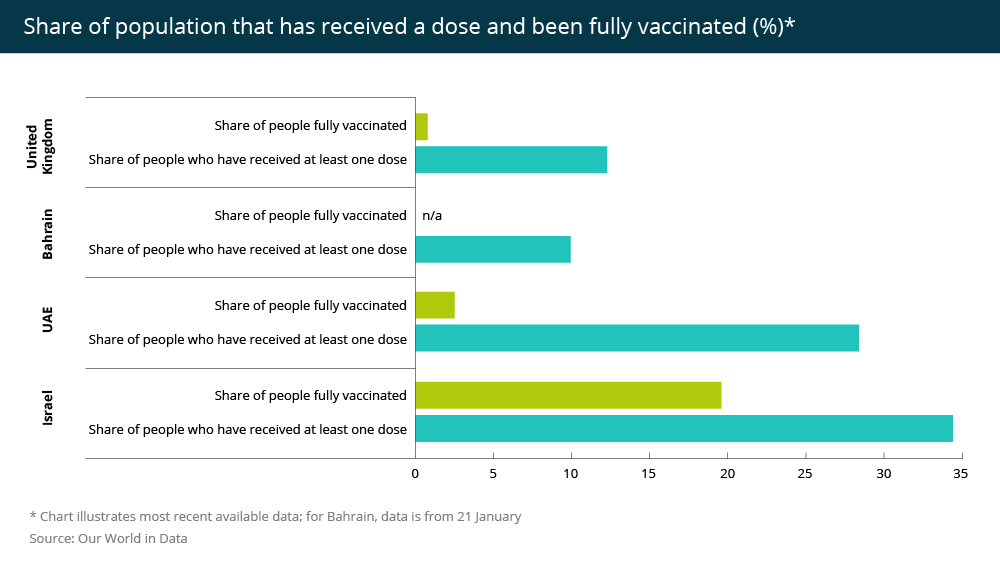

In Israel and the UAE (the two countries vaccinating the fastest worldwide), approximately 35% and 29% of the population, respectively, had received at least the first shot of a COVID-19 vaccine by 31January. Israel aims to vaccinate most of its adult population by mid-March. The UAE aims to vaccinate 50% of its population by the end of March. At current vaccination rates, the two countries are likely to meet their targets.

There are political and economic drivers behind Israel and the UAE’s herculean inoculation efforts. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is intent on mass vaccination, seeking a progressive return to normalcy to boost his chances in the 23 March parliamentary elections. The UAE is among the region’s economies most reliant on tourism, international trade and the movement of people across borders. The Dubai emirate, the economy of which contracted by 6.2% in 2020, has made every effort to keep its economy open to international tourists and travellers. The UAE hopes to quickly reopen its borders by vaccinating on a large scale.

Both countries have highly developed healthcare infrastructure with good access to vulnerable populations – aided by digitisation – which has helped distribute the vaccine rapidly. They are also rich by regional standards. Israel-based newspaper The Times of Israel on 16 November 2020 reported that Israel agreed to pay 40% more than the US and EU for the Pfizer vaccine. In addition, the UAE participated in the three-phase trial of the SinoPharm vaccine, granting itself preferential access to the vaccine when it was completed. The UAE has also secured stocks of the Pfizer vaccine – though deliveries have experienced delays – and on 21 January approved the Sputnik V vaccine for emergency use.

In addition, both countries have small populations (at just under 10m) distributed over small territories. Israel is just 21,000 sq km. The UAE is four times larger, at 83,000 sq km, but most of its population is concentrated in a few cities across the northern half of the country. These geographical characteristics have significantly aided the logistics of both vaccination campaigns.

…and the have nots

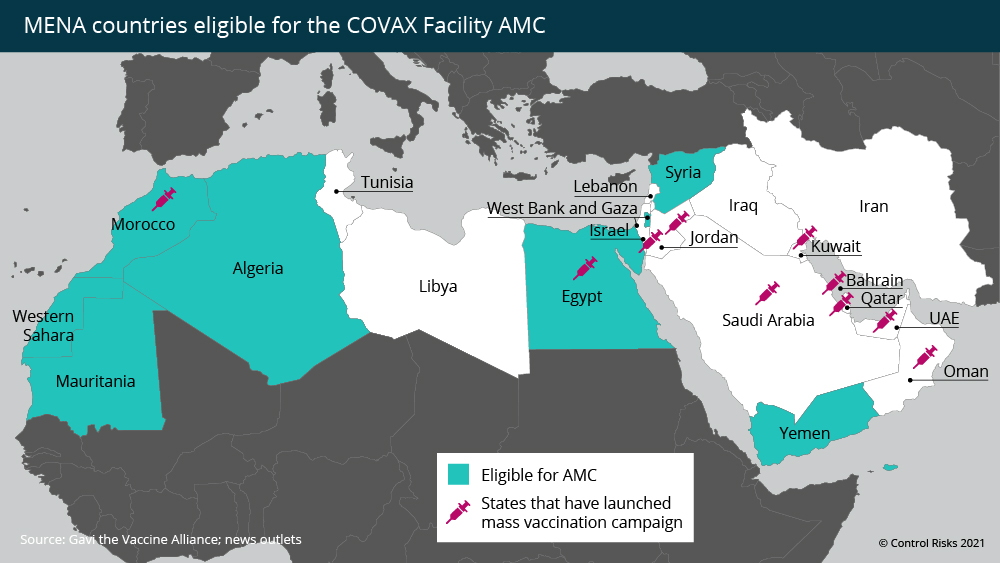

Should their respective vaccine rollouts continue according to plan, Israel and the UAE will likely start gradually easing COVID-19 constraints in a couple of months. However, few countries in MENA will be able to follow their lead. Many have poorly functioning healthcare systems, scant public funds and large populations spread over large territories. As many as eight states in MENA are eligible for the Advance Market Commitment (AMC), which grants access to the COVID-19 Global Vaccines Access (COVAX) Facility at a reduced cost.

States participating in the COVAX Facility are expected to receive enough doses to vaccinate at least 20% of their population in the long-term; this will not sufficiently curtail the virus’s circulation. Most states are supplementing the doses received from the COVAX Facility with advance purchase agreements (APAs). Many MENA states, however, will not have the necessary funds to secure access to enough doses through APAs, and inoculation campaigns are yet to begin in ten MENA states.

Slow vaccination campaigns run on irregular deliveries of small batches of doses will mean that operational disruptions and further waves of infections will likely occur across many MENA states throughout 2021. MENA states that have large populations, insufficient healthcare infrastructure and/or limited funds to acquire doses – including Iraq, Egypt, Lebanon and Iran – will continue experiencing significant COVID-19-induced disruption. COVID-19-related disruptions and restrictions will intensify as more virulent variants spread globally. In many of these states, pandemic-induced disruptions will contribute significantly to civil unrest, as the socio-economic and public health environments deteriorate, and citizens take to the streets to hold their governments accountable.

States in conflict – including Syria, Yemen and Libya – will face the greatest difficulty in delivering mass vaccinations. In these conflict zones, COVID-19 may never be eradicated at all, creating lasting pockets of COVID-19 in the same way smallpox, polio and measles have lingered in some parts of the world.

COVID-19 vaccine diplomacy

COVID-19-related humanitarian assistance and vaccine diplomacy (leveraging vaccine supplies to promote foreign policy objectives) will likely increase once potential donors manage to largely complete their own vaccination programmes in the second half of 2021. Some of this aid will likely come from within MENA. For example, the UAE will capitalise on its position as a global logistics hub to distribute vaccine doses to the worst affected countries in the region and globally.

Outside of MENA, China and Russia will likely seek to capitalise on vaccine deliveries to strengthen their influence and diplomatic ties in the region. China positioned itself similarly in the early months of the pandemic; for instance, Beijing in April 2020 signed a USD 265m deal with Riyadh to support COVID-19 testing capacity on short notice. During the vaccine development phase, China secured the participation of six MENA states – including the UAE – in clinical trials of its Sinopharm, Sinovac and CanSino vaccines. Similarly, Russia secured the UAE’s participation in clinical trials of its Sputnik V vaccine.

The vaccines developed by Russia and China can be stored at much higher temperatures than the Pfizer vaccine (which requires extremely cold storage) and are therefore good candidates for distribution in countries where setting up complex supply chains may be difficult. Given that these vaccines are produced by state-backed companies, supply levels and deliveries can be adapted to satisfy policy objectives rather than strict profit targets. Ultimately, Moscow and Beijing could emerge from the COVID-19 vaccination period with stronger ties with several MENA states, particularly in the healthcare sector.