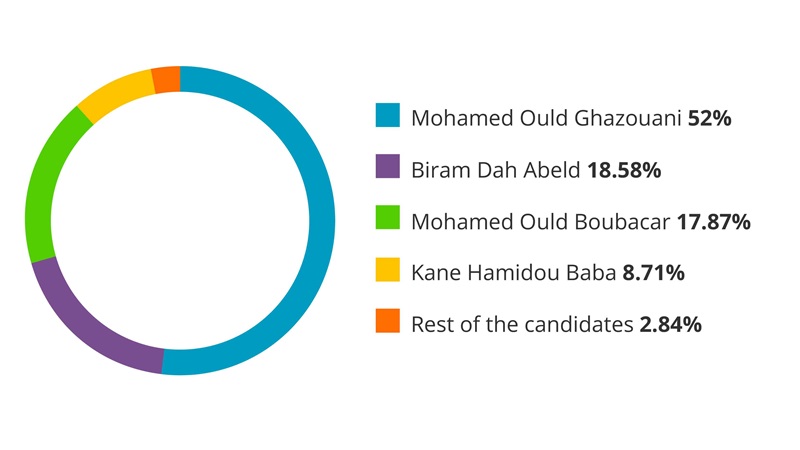

The government-backed candidate, Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, was elected president with 52% of the vote in the 22 June election. This represents the first democratic transfer of power since independence in 1960.

Three key points

1. Ghazouani is a close ally of outgoing President Mohamed Ould Abdelaziz. His election will preserve overall continuity in domestic, security and foreign policy over the coming years.

2. It remains unclear how Ghazouani will manage his ties to Abdelaziz, who vowed to retain a role in the country’s politics. Such uncertainty will place upward pressure on political stability risk.

3. The security environment will be characterised by protests against Ghazouani and activity by militants with a heightened intent to undermine the country’s stability. However, a sharp security deterioration remains unlikely.

Contested results

Ghazouani came in ahead of several opponents, including anti-slavery activist Biram Ould Dah Abeid and a former prime minister, Mohamed Ould Boubacar, who was backed by the Islamist party Tawassoul. Ghazouani, who is expected to be officially sworn in on 2 August, has been a close ally of the outgoing president since they participated in the 2005 coup d’état and led another coup d’état in 2008 that brought Abdelaziz to power. Ghazouani was Abdelaziz’s military chief of staff for ten years and then defence minister for several months.

Ghazouani was officially supported in his election run by Abdelaziz, which raised tensions between the government and the opposition in the months preceding the vote. The opposition accused the government of hijacking the electoral process in favour of Ghazouani. Tensions revolved around several issues:

- The opposition objected to the composition of the Independent National Electoral Commission (CENI), which was tasked with organising the election. It called for its dissolution, which the government rejected.

- The government rejected the opposition's request to authorise the deployment of EU observers during the polls. It only allowed the presence of two EU experts to provide technical advice.

- The CENI awarded the contract for the production of the ballots to a Mauritanian company owned by a businessman close to Abdelaziz.

Following the announcement of the results, three opposition candidates lodged an appeal with the constitutional council citing voting irregularities. On 24 June the police closed the headquarters of the electoral campaigns of four opposition candidates and arrested dozens of protesters who demonstrated against the results in the capital Nouakchott. The government also briefly cut off internet access.

Votes received per candidate (% of total)

Stability outlook

Ghazouani campaigned on the promise of maintaining stability and preserving security. There was an uptick in terrorist activity between 2005 and 2011 by Islamist groups, which benefited from under-governed, long frontiers with the Sahel and Maghreb regions, a fragmented social fabric and widespread socio-economic grievances. Since Ould Abdelaziz became president in 2009, he has led counterterrorism efforts that included both a crackdown on Islamists, the creation of new intelligence and military capabilities and an encouragement of theological revisions by radical scholars and groups. These measures were coupled with increased security cooperation with the US, European countries and neighbours on enhancing border control.

With his military background and close relationship with Abdelaziz during the latter’s ten-year tenure, Ghazouani is likely to maintain policy continuity, focusing on maintaining internal stability by limiting the militant threat, constraining political opposition, enhancing border security and collaborating with Western and regional countries on maintaining security in the wider Sahel region. Ghazouani is also likely to maintain the government’s pro-business attitude, particularly around the development of the giant Tortue-Ahmeyim offshore natural gas complex on the border with Senegal, a project in which many foreign companies are involved.

Nevertheless, uncertainty looms over how the new president will manage his relationship with Abdelaziz over the coming years. Ould Abdelaziz has repeatedly vowed to retain a role in the political system, though he has not defined what this role would be. He is motivated by a desire to retain influence and protect his and his family’s interests by preventing reprisals from political and business opponents during his successor’s rule. Ould Abdelaziz could, for example, seek to return to power in the 2024 elections. The outgoing president in the past six months made significant changes within the military, pointing to a degree of mistrust and concerns about his future after he steps down. Most notably, on 21 February he reorganised the presidential security battalion (BASEP), which saw several officers loyal to him promoted.

The coming months will show to what extent Ghazouani will tolerate Abdelaziz’s attempts to remain influential in domestic politics. Any infighting between the two figures would pose increased threats to the country’s political stability.

Security challenges

Following the announcement of Ghazouani’s victory, riots broke out in Nouakchott and protesters opposed to Ghazouani clashed with the authorities. The government reportedly detained 100 protesters from Sub-Saharan African countries, and the foreign ministry summoned the ambassadors of Senegal, Gambia and Mali, urging them to tell their nationals to refrain from engaging in protests in Mauritania. The authorities blamed the unrest on a foreign plot aimed at destabilising the country, a sensitive matter in a society that is fragmented along ethnic lines, namely Arab-Berbers, Haratines (descendants of slaves) and Sub-Saharan Mauritanians.

Further occasional protests against Ghazouani’s rule over the coming months are likely and will involve violence as the authorities will be determined to crack down on protesters and political dissent. This will be driven by a strong opposition to Ghazouani – 48% of the voters voted against him. Ethnic tensions will remain heightened as the new president comes under pressure to combat the practice of slavery, which continues to affect around 90,000 people in Mauritania, according to the Global Slavery Index. Protests are, however, unlikely to be large enough to destabilise the government or trigger a sharp deterioration of the security environment.

The increasing threat posed by militant groups in the wider Sahel region and the government’s challenges in preventing cross-border trafficking – including of weapons – along Mauritania’s long borders mean that militants will have an increased intent to target the country. More specifically, instability in Mali will pose an immediate security threat to Mauritania over the coming years, given the challenges in securing the two countries’ shared border.

Part of the Big Picture Series, taken from Seerist.