Disputes involving sovereign states are on the rise. The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes logged a record 58 new cases in 2020, for example, compared to an average of just under 50 per year over the previous five years. Now more than ever, understanding a sovereign state’s asset profile will form a critical part of the dispute resolution strategy for any party pursuing a remedy for contract frustration via litigation or alternative dispute resolution.

The rise in disputes involving sovereign states stems from the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. From supply chain disruption to the availability of human capital, the pandemic has tested even the most resilient businesses. While a return to some form of commercial normality is anticipated in a small number of wealthy nations, the economic impact of the pandemic will continue to be felt by businesses across the globe. The effect of the pandemic has been particularly acute for the debt profiles of many nation states, especially in the developing world. According to World Bank estimates, in 2020 government debt of emerging markets and developing economies reached 60.8% of GDP, an increase from 52.1% in 2019.

Navigation enforcement challenges

Enforcing an award against a sovereign state presents unique challenges for counsel and investigators. The sovereign immunity doctrine, which emanates from the concept of sovereign equality and independence of states, protects most state-owned assets from being seized. This includes properties held by diplomatic and consular missions of a sovereign abroad, and assets held by its central bank. That said, sovereign immunity does not typically extend to a state’s commercial activities, such as:

- The acquisition of immovable property

- The purchase of stakes in private companies

- Investments in government-owned airlines

- The repayment of commercial loans

- Military procurement

- Embassy repair contracts

A well-planned asset recovery strategy will therefore prioritise the identification of assets most likely to fall beyond the protections of sovereign immunity. An asset’s classification in terms of its commercial use, liquidity, transferability, location and prestige value informs how investigative resources can be allocated towards the most valuable endeavours in the most cost-effective manner.

Ultimately, the claimant bears the onus of proving the nature, and sometimes intent, of activities and assets held by a sovereign; and investigators will play a major role in gathering the evidence required to demonstrate this.

SOE Ownership and proximity

Another challenge involves potentially seizeable assets that are not directly owned by a sovereign state, but rather by a separate legal entity such as a state-owned enterprise (SOE). SOEs often own a state’s most valuable assets and many have footprints outside their national jurisdictions.

In such a case, a party must demonstrate that the entity is sufficiently interconnected with the state that its assets can be seized in order to satisfy an award against the sovereign. For example, in July 2019, the US Court of Appeals found that Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), Venezuela’s state-owned oil company was “so extensively controlled by its owner [the Republic of Venezuela] that a relationship of principal and agent is created,” thus making it an alter ego of the sovereign and allowing the creditor to attach PDVSA’s assets to satisfy its judgement award against the Venezuelan government.

A counterexample can be found in an earlier 2012 ruling by the Court of Appeal of Jersey which found the Congolese mining SOE La Générale des Carrières et des Mines (Gécamines) and its activities to be insufficiently intertwined with that of the sovereign – they had separate budgets, debt and tax liabilities – to be considered as an alter ego of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s government. As a result, the claimant was unable to seize Gécamines’ assets to satisfy the government’s outstanding debt.

Information obtained from retrieved corporate filings, government announcements and media articles – such as the corporate structure used to hold certain government assets as well as the extent of the role played by the sovereign in the management of SOEs – can help legal teams to build alter ego arguments, showing that a state-owned company is not functionally and financially independent and operates as an extension of the State. Targeted enquiries among contacts with direct knowledge of a target SOE’s internal workings can also be critical to building up an understanding of its management and level of independence from the State, especially in jurisdictions where public records are not widely accessible, such as Venezuela and Congo-Kinshasa.

Asset mapping

A crucial early step in any sovereign asset trace is to map out the assets that are likely exempt from traditional sovereign immunity protections. Based on Control Risks’ past experience, the most attractive targets are assets owned by the state but used for commercial purposes as these do not enjoy sovereign immunity. They can be immovable assets, such as real estate located in debtor-friendly jurisdictions – which, depending on the award, would typically include common law and Western European jurisdictions – and movable ones such as vessels and aircraft that travel outside of the country’s national borders.

Immovable assets

Immovable assets, such as real estate held outside the sovereign entity’s home jurisdiction, are particularly attractive as they are usually exempt from state immunity. This is in marked contrast to liquid assets, for which targeted governments have often successfully argued in court that they cannot be seized as they are being used for sovereign purposes.

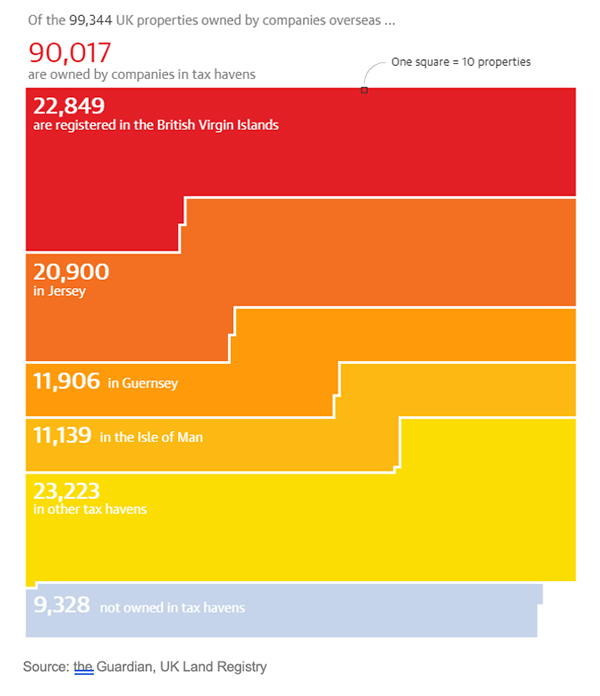

Thousands of high-value properties in the UK are held by offshore entities – a December 2016 Transparency International report found that 91% of overseas entities that own property in London are registered in secrecy havens. The same study found that over 75% of land titles linked to politically exposed persons are owned by companies registered in either Panama or the British Virgin Islands (BVI).

Foreign-owned UK properties

Investigators can leverage transparency initiatives such as the 2018 Registration of Overseas Entities Bill, which seeks to create a publicly accessible register of beneficial owners of overseas entities that own UK land, to link sovereign states to immovable assets that can then be frozen.

Planning applications or tenders for improvement works can also be used to connect property to a government and provide further context on its use. In the tax dispute between Cairn Energy Plc and the Government of India, the former’s legal team successfully used information including public tender documentation to win an application in the French courts to freeze some EUR 20m of property in July 2021.

Movable assets

Movable assets such as aircraft or vessels are another desirable category of assets. In addition to the monetary value attached to them, and the possibility of seizing them as they move into friendly jurisdictions, they may also hold symbolic importance for the country. As a result, freezing them, even for a short period of time, can force a sovereign debtor into settlement.

In 2012, the ARA Libertad, a training ship owned by the Argentine Navy, was prevented from leaving the port of Tema, Ghana. NML Capital, a subsidiary of hedge fund Elliott Capital Management, had successfully obtained an injunction from the Ghanaian government to seize the ship as partial repayment for the USD 20m debt it was owed by the Argentinian government following Argentina’s 2001 default. NML Capital’s legal team had been following the Libertad’s course closely, waiting for it to enter waters where judgments awarded by UK and US courts could be enforced.

In a similar vein, in August 2019, an Air Tanzania Airbus A220-300 was grounded upon landing in Johannesburg on a regularly scheduled flight. The grounding order was made in relation to a land compensation dispute dating back to 1982 between the government of Tanzania and a South African farmer, Hermanus Steyn. The aircraft was later released after a successful appeal by the Tanzanian government. Previously, in 2017, the Canadian construction firm Stirling Civil Engineering had seized the airline's new Bombardier Q400 plane in Canada before it was delivered in Tanzania over a USD 38m lawsuit. The Q400 was released in March 2018 after Tanzania's prime minister and attorney general negotiated its release. The details of the settlement were not publicised, but the leverage afforded to Stirling Civil Engineering in its dispute is unequivocal.

A more recent example is the seizure of a Falcon 7X aircraft used by Congo-Brazzaville’s president Denis Sassou Nguesso as it landed in the airport of Bordeaux in June 2020. The French courts authorised the seizure of the plane in the context of a 25-year dispute between the Republic of the Congo and Lebanese businessman, Mohsen Hojeij. Hojeij had been authorised to seize all assets belonging to the Republic of the Congo’s government except “those used in the exercise of the State’s diplomatic mission functions” and successfully argued that the plane fell outside of the diplomatic immunity as it was mostly used by President Denis Sassou Nguesso for personal trips rather than official visits.

Other assets

Beyond the asset classes discussed above, other attractive assets include:

- The acquisition of immovable property

- The purchase of stakes in private companies

- Investments in government-owned airlines

- The repayment of commercial loans

- Military procurement

- Embassy repair contracts

For creditors, overseas bank accounts held by government are, at face value, appealing targets. However, banking privacy laws in most jurisdictions prevent private outfits from accessing bank account details. One potential work around is to look for accounts used for specific activities such as servicing interest payments on bonds it has issued or paying overseas royalties.

In the 2006 case FG Hemisphere Associates v. République du Congo, creditors seized royalties and tax obligations owned by state-owned oil companies. The court determined that the royalties and tax revenues constituted “commercial activities” as they were found to have previously been used to repay a commercial debt to a US-based lender.

In the 2008 case Orascom Telecom Holding SAE v Republic of Chad, a bank account was being used for the “purpose of a commercial transaction” and was not found to be covered by sovereign immunity, despite the purpose of the transaction being to benefit the state. Indeed, the account had been set up to channel Chadian oil revenues intended to repay sovereign loans contracted with the World Bank.

By reverse engineering the receipt of funds by, for example, a bondholder, we can identify the account used to make these payments and thus associate it conclusively to the sovereign, regardless of the entity that is legally registered as holder of the funds. Indeed, this allows investigators to leap over complex corporate structures built around shell companies – often created as asset-protection measures – and attach the assets directly to the debtor.

Data sources

Obtaining the most from a client’s award

The ultimate goal of an asset tracing exercise is to maximise the funds recovered by a creditor following an award. In some cases, this may be achieved by identifying immovable and movable assets to be seized and later sold. However, where a State has few assets held outside its home jurisdiction, or where it has successfully argued in court that they are covered by sovereign immunity, a creditor may be forced to adapt its legal strategy, and instead apply pressure on the State that can push them towards settlement.

The most effective way to bring the sovereign state to the negotiating table tends to be by targeting high profile flagship assets. For example, by freezing assets that paralyse an SOE’s operations. This can cut off vital revenue streams for a State, and alienate foreign investors and potential business partners who are sensitive to the risks of engaging in commercial relations with the sovereign debtor. Or, successfully seizing movable assets used by senior government officials, such as the Head of State’s private jet, can create embarrassment, gain media traction, and deprive a key decision maker of the use of a luxury asset. These can all be instrumental in applying pressure to the sovereign debtor, and ultimately force it to agree to a favourable settlement for the creditor.