Analysing data from Seerist, we have noted four concerning trends:

1. The number of attacks has consistently grown in the region since 2015.

2. Islamist militancy has spread rapidly across the Sahel in recent years.

3. Attacks have become increasingly deadly.

4. Private organisations and business personnel are increasingly attractive targets.

Rise in number of attacks

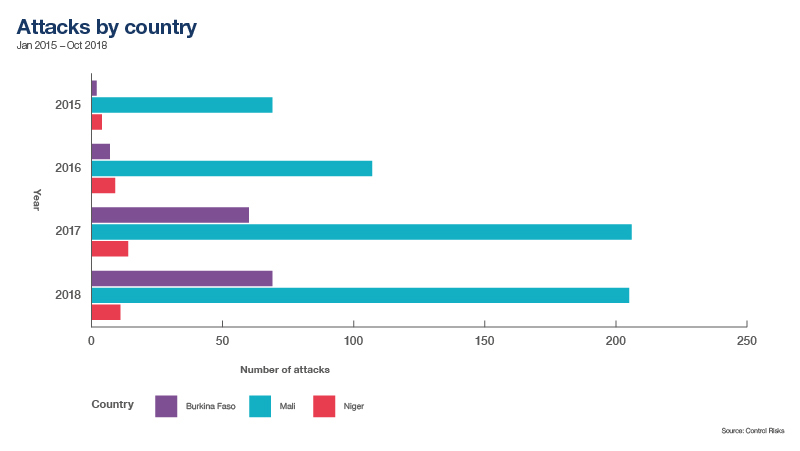

The number of attacks in the Sahel has grown rapidly since 2015, especially in Burkina Faso and Mali. Control Risks recorded 74 attacks in 2015, compared with 285 so far in 2018. The reasons for this rapid growth are diverse and interconnected, but the primary factor is the ability of Islamist militant groups to adapt to the local environment. Prominent local leaders such as Iyad Ag Ghali and the late Amadou Koufa facilitated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM)’s recruitment efforts by giving the group access to – and credibility among – the local Tuareg and Fulani ethnic groups, respectively. Both JNIM and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), the main militant coalitions active in the region, have successfully adapted elements of their ideology to local dynamics in the Sahel. These groups have also been able to capitalise on local conflicts, popular frustration with the lack of state presence, and poor governance or abuses committed by local officials.

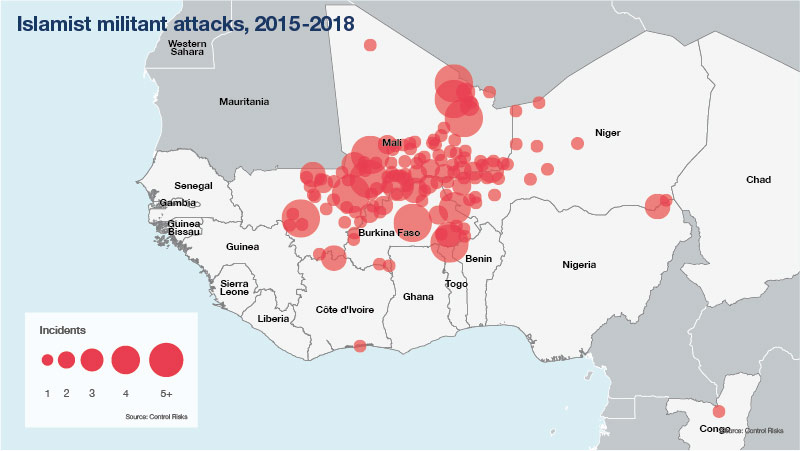

Trend 2: Regional expansion

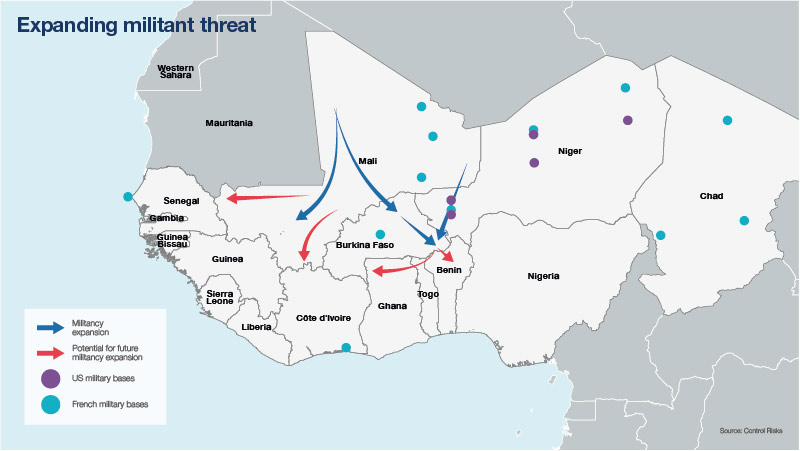

Islamist militancy has hit Mali hardest, with the country accounting for 75% of all incidents since 2015. However, Control Risks’ data illustrates the rapid spread of Islamist militancy across the Sahel more widely in recent years. Militant groups have either established new cells or carried out attacks in previously unaffected areas, and now operate over an area of nearly 1m sq km. In the first quarter of 2015, 80% of incidents took place in the three regions of Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu in northern Mali; in the first quarter of 2018, they were divided far more evenly across three countries and 11 regions.

This expansion has affected areas where the terrorism threat was previously low. In Mali, Islamist militants have established new strongholds in the central regions of Mopti and Ségou. Some remote areas outside of regional towns are now largely out of reach of state authorities. In Burkina Faso, homegrown militant group Ansarul Islam in late 2016 emerged in northern regions of the country bordering Mali. More recently, the threat has spread east, with the emergence of two new cells near the borders with Niger and Benin. Each group has been quick to acquire the standard playbook of terrorist tactics – including kidnaps-for-ransom and improvised explosive device (IED) attacks – dramatically altering the security environment in these regions.

Trend 3: Deadlier attacks

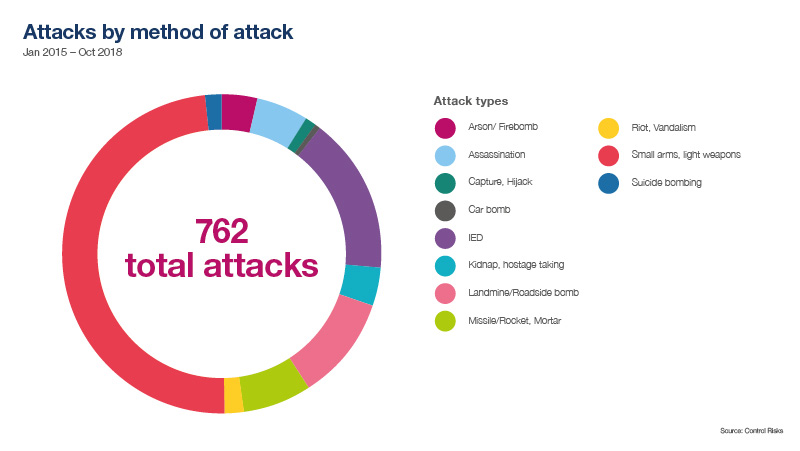

Islamist militant tactics in the Sahel resemble those of a guerrilla insurgency. Since the French military intervention in Mali in 2013, militants have abandoned hopes of gaining and holding territory. Instead, they mainly operate in small, mobile teams to evade surveillance, travelling by motorbike in remote, sparsely populated areas, and usually avoiding direct confrontation with security forces.

Increased aerial surveillance has discouraged Islamist militants from mobilising large numbers of combatants to target a well-protected site. This reduces the likelihood of an attack of the type that targeted an industrial gas complex in In Amenas (Algeria) in January 2013. Instead, incidents now usually involve a small group of gunmen (often no more than ten) on motorbikes carrying out a “hit-and-run” attack on an isolated and poorly protected target. We have recorded 374 such attacks since 2015 – nearly 50% of total incidents.

However, militant groups have mastered the use of IEDs and become increasingly effective at staging roadside ambushes. The number of roadside IED and landmine attacks has spiked since 2017. They have also resulted in significantly more fatalities: 170 so far in 2018, compared with 86 last year, with the number of fatalities occurring during each IED attack more than doubling. This is forcing organisations across the region to rethink their approach to overland movements. Suicide and car bomb attacks remain rare, with four incidents recorded in 2018. With one exception (a car bomb attack in the Burkinabè capital Ouagadougou in March), these all occurred in northern Mali during high-profile attacks.

Trend 4: New targets

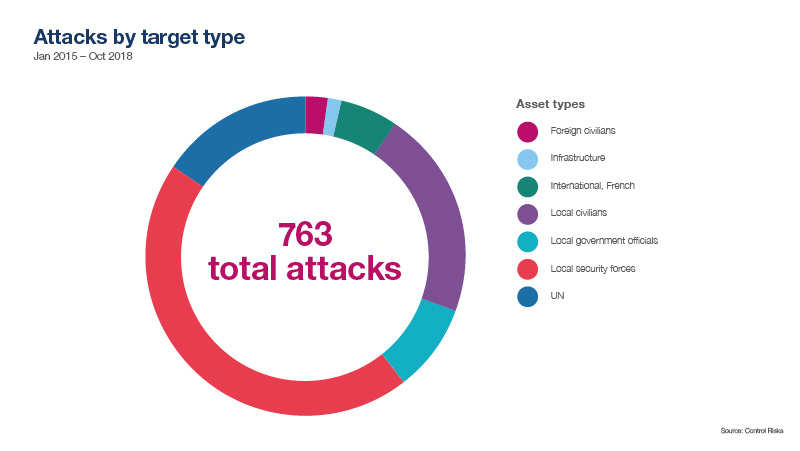

Unlike other militant groups in Africa, such as Nigeria’s Boko Haram, Sahel-based groups have not sought to create indiscriminate fear. Their ideology, inherited from al-Qaida, is more selective. International military forces, such as UN peacekeepers, French and US counterterrorism troops, and the local government forces that cooperate with them, are the main target groups. Together, these groups were the targets of two-thirds of all attacks we recorded. Militants have additionally directed attacks against local government officials and representatives of government agencies, in an attempt to drive out state authorities. They have also targeted local civilians who oppose them and/or provide intelligence to counterterrorism forces.

Private organisations have a more limited presence in the region and are not attacked nearly as frequently, targeted in only 6.3% of all incidents. However, private organisations and business personnel are attractive targets for militants. This is particularly the case for Western organisations, which militants have likened to “crusaders” and accused of “looting” local resources. Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in May explicitly threatened Western companies operating in the Sahel for the first time. However, Chinese contractors in Mali have also been targeted, suggesting that the perpetrators do not clearly distinguish between target nationalities

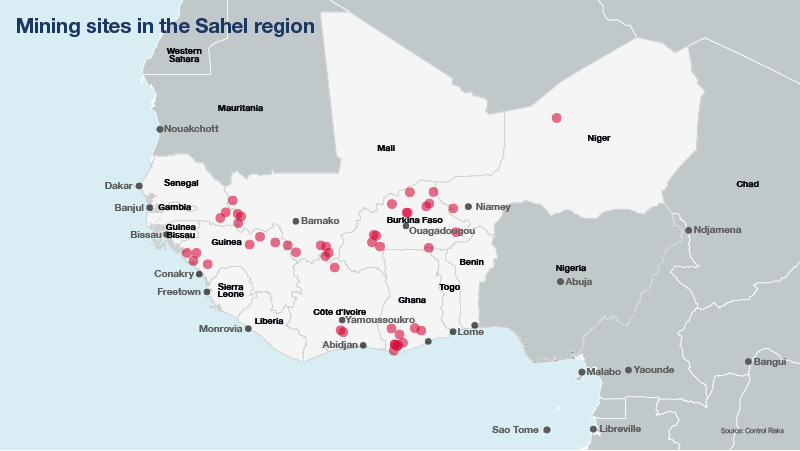

Attacks on capital cities (seven since 2015) have mostly targeted locations frequented by expatriate personnel during their free time, such as restaurants, bars or resorts. NGO personnel, travelling more regularly in remote regions, have been more exposed, as have contractors working on road, power or other infrastructure projects. Gold mining operators – the main foreign investors in the region – have been impacted, with Control Risks aware of at least six attacks targeting mining companies or personnel since 2015. Operators in remote areas are also at risk of opportunistic raids, during which militants seek easy access to provisions and assets such as fuel, vehicles and cash to fund their activities. These types of raids often go unreported. Benefiting from a favourable terrain, the new cells in eastern Burkina Faso have the potential to spill over into northern Benin, Togo or Ghana. In Mali, militants could seek to expand further along the borders with Burkina Faso and Mauritania, which could ultimately put them within reach of mining sites. There are also concerns that Mauritania, which has not seen a major militant attack since 2011, could again become a target as it assumes an active role in the G5 Sahel counterterrorism force. Oil and gas investments in Senegal and Mauritania remain outside the reach of these groups, but over time militants may increasingly wish to attempt high-profile attacks in Dakar or Nouakchott.

Operating in the region

Foreign organisations operating in the Sahel will have to contend with the threat of terrorism for years to come. France’s contribution to counterterrorism, though of continued importance, will be insufficient to eradicate militant groups. The G5 Sahel, a new regional counterterrorism force, will take several years to become fully operational. In the short term, the impact of terrorism on foreign investment will be most significant in Burkina Faso. Ouagadougou is the capital in the Sahel to have suffered the most Islamist militant attacks, with three separate incidents in January 2016, August 2017 and March this year killing a total of 57 people. Mineral deposits in Burkina Faso are also dispersed across the country, with several projects located in high-risk areas. This contrasts with mining projects in Mali, which are clustered in the south-west, a region that has been sheltered from attacks. Organisations should continue to watch for the spread of militancy to new areas. Militant groups have typically thrived in remote border regions with weak state authority, poor local infrastructure and a pervasive sense of marginalisation. They have sometimes grown out of local disputes over authority, or profited from conflicts to gain new recruits. Companies should watch for similar dynamics in the areas in which they operate.

The evolving nature of the terrorism threat in the Sahel will continue to necessitate an up-to-date understanding of militant hotspots, targeting patterns and modus operandi. A robust security approach will also require an awareness of local and regional dynamics, how they play out on the ground, and their likely operational impact.

Contact us to learn about concrete measures operators can take to limit their exposure to terrorism in the region: [email protected]

Authors

- Vincent Rouget, Senior Analyst

- Mikolaj Judson, Analyst