Built Environment & Infrastructure Risk Management

-

Search

India has made impressive strides in recent years towards becoming an easier place in which to do business. For the first time, it featured as one of the ten countries that had improved the most in a year in the World Bank’s 2018 Ease of Doing Business (EODB) rankings. Tax reforms played a major role: the number of annual payments companies need to make reduced by nearly half, while the time taken by tax audits decreased significantly. However, at 100th place out of 190, India still has a long way to go to achieve Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s goal of breaking into the top 50. We expect a further push to improve the score ahead of the 2019 general elections.

However, for India-focused CxOs looking for support with strategic business decisions – such as where to invest and how to reallocate resources – the EODB rankings offer only limited insights. The study is based on assessing the business environment in only Delhi and Mumbai. Anyone who has done business in India knows that these two cities are hardly representative of the whole country.

With the World Bank’s support, India created the Business Reform Action Plans (BRAP), a set of policy targets for the country’s 29 states. The results, which are published annually, create significant public attention and intense rivalry for the top ranks, measured by the degree to which the federal government’s reform agenda is implemented. This is competitive federalism – an initiative to make states compete with each other for investment – in action.

At times, the BRAP rankings show surprising results, reminding us that statistics need to be complemented with knowledge of the underlying conditions, but also highlighting that opportunities can be found beyond the usual business clusters. The most recent results were published in July 2018, awarding Chhattisgarh, affected for decades by a violent guerrilla movement, a 97% implementation score. West Bengal, a state where labour unrest has frequently hampered business, achieved 95%. We can of course still find some of the usual favourites – Andhra Pradesh returned as the top performing state.

Business-related policies primarily implemented at state level

The EODB and BRAP focus on policies, rules and regulations, and fail to account for factors that are more difficult to quantify, but are equally important to strategic decision-making. Tamil Nadu, for example, achieved a BRAP score of 91%. While the state has been an attractive investment destination for decades, the death of its long-term chief minister Jayalalithaa in December 2016 led to political factionalism and a power vacuum, ultimately increasing operational risks for companies.

As an illustration, in late 2017, car manufacturer Nissan sued the Tamil Nadu government for USD 770m in investment incentives that the state had guaranteed in 2008, but eventually refused to disburse. In a separate move, another automaker, Kia Motors, announced in May 2017 that it would set up a new USD 1.1bn factory in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh, rather than expand its existing facilities in Tamil Nadu. In a much publicised Facebook post, an independent consultant for Kia claimed the decision was influenced by the fact that politicians in Tamil Nadu “demanded 50% more than the official cost of the land as a bribe”.

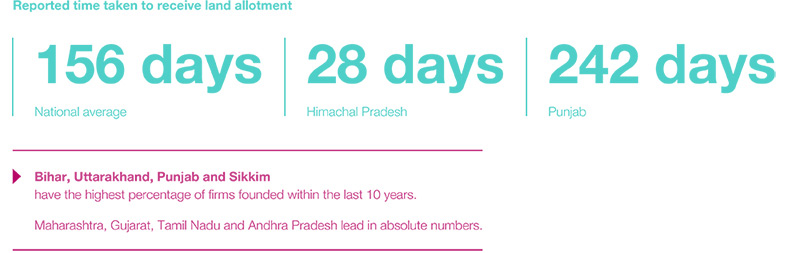

Clearly, ground-level knowledge and political–economic foresight have to complement macroscopic analysis when it comes to strategic decision making. The Indian government acknowledges that state-level macroeconomic data needs to be complemented by enterprise-level realities, as illustrated by a large-scale business survey published in August 2017 which found, for example, dramatic differences between states when it comes to the time to receive land allotments.

Source: Ease of Doing Business – An Enterprise Survey of Indian States, September 2017

The support that indicators such as the EODB and BRAP, and their related reforms, receive at the very top of the Indian government is remarkable. As such, our overall outlook on the efforts to improve India’s business climate remains positive. When it comes to making strategic decisions, however, it is imperative that decision makers look beyond written policies and macro indicators. Even comparing among the states may lead to oversimplification. Instead, companies should identify their goals and needs, and then carefully assess the degree to which these can be met – taking into account the ground realities of reforms, regulations and local dynamics.

It is still a truism to call India a highly complex market. To deliver success, decision-makers need to develop bespoke strategies that combine relentless focus on identifying opportunities with pragmatic understanding of the situation on the ground, including local dynamics and regulatory implementation. It is certainly getting easier to do business in India – but figuring out how to move decisively still takes considered thought and planning.

Author