The intelligence gap

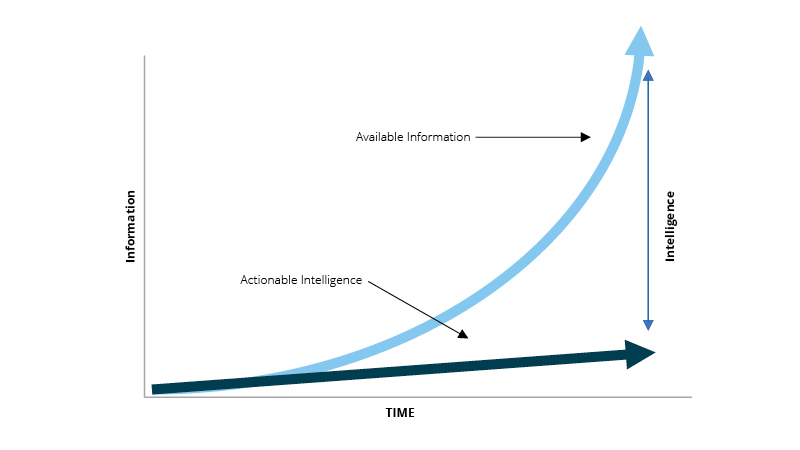

Today’s threat actors evolve with one foot in the online domain. Too often evidence of a growing threat is unearthed in a threat actor’s online environment after an incident that impacts security, integrity and reputation. Risk and security professionals strive to be proactive in defending their organisations, but so far the private sector has not found a unified approach to online threat analysis. With the enormous growth in online traffic and data in the indexed, deep and dark webs, the challenge is to find intelligence amid all the noise. Across sectors, organisations are now starting to grapple with the complexity of this environment in an attempt to bridge the what has become known as the intelligence gap (figure below).

Monitoring threats online – a dichotomy of words and actions

The internet is noisy, violent language and content is commonplace. This makes it difficult for security and risk teams to make confident assessments on the likelihood and credibility that threats made online will be acted on in the ‘real-world’. It is equally true that online platforms are increasingly where would be actors are radicalised and attacks are originated and planned.

1. Open-source - newsfeeds, blogs, open forums

2. Social media - major and minor communication platforms

3. Deep and dark web platforms - chat applications, criminal forums, marketplaces, ideological community forums

Monitoring the internet for threats requires a comprehensive understanding of the span of these sources, in conjunction with expertise in how to interpret the vast quantities of information.

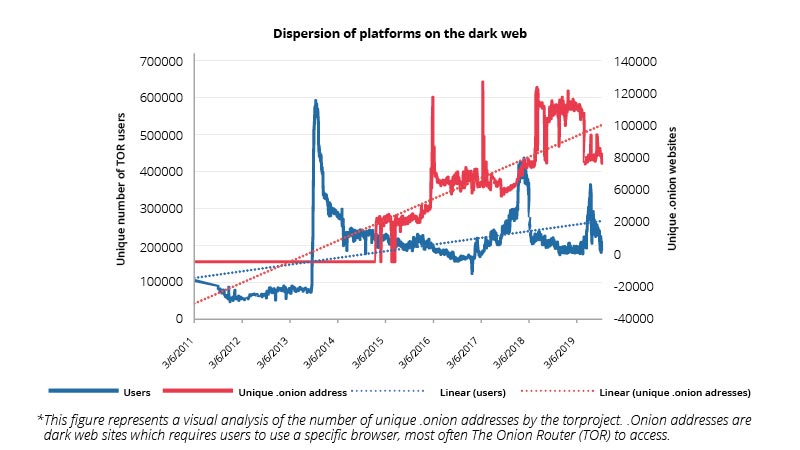

According to figures compiled by the social media aggregator Hootsuite there are 4.3 billion internet users worldwide, including 3.4 billion social media users. Estimates suggest that the deep web is up to 500 times larger than the indexed web - itself composed of more than 4.5 billion websites. Within the deep web, the dark web is thought to have about 100,000 websites.

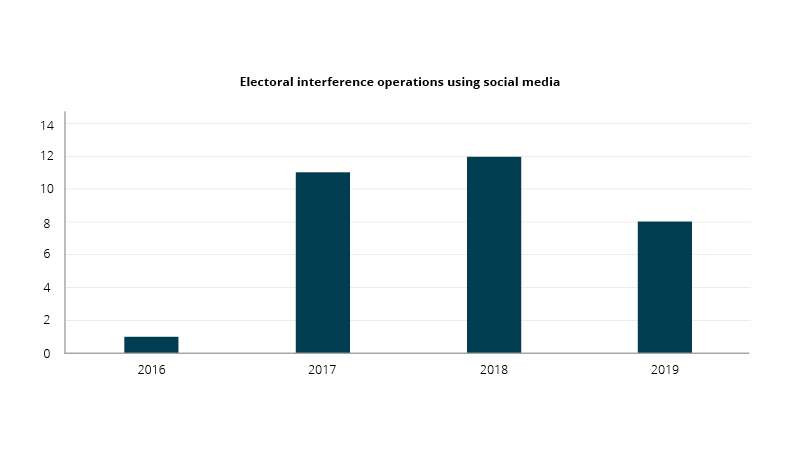

The vastness of the online domain is further complicated by the speed of its evolution. Sources taken down are almost immediately replaced by several alternatives, especially across criminal and violent communities (see figure above) . Online communities find new platforms when existing ones are compromised and ideologies continue to develop. The language used online evolves constantly, generating new vocabularies which complicate detection strategies such as linguistic/semantic analyses for expressions of hostile intent. Teams responsible for monitoring and reporting online security threats must constantly revise and expand their understanding of platform and language evolution.

Ideologies and motives in the online space are fluid

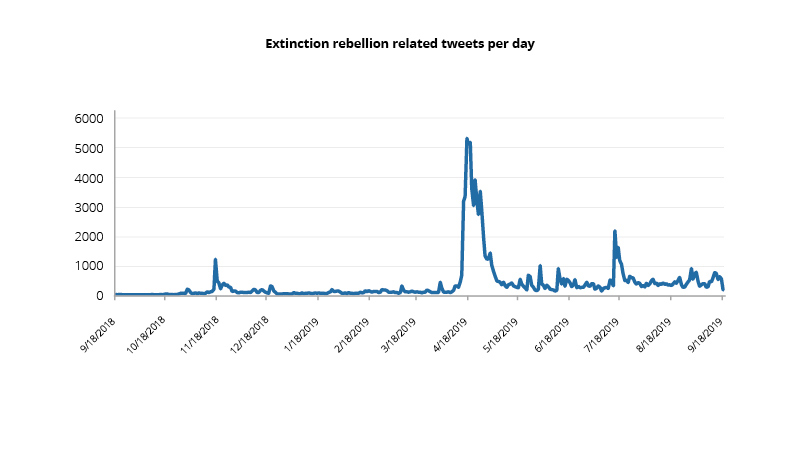

Ideologies in the digital space have become fluid, sometimes blurring the line between those who are radicalized and those who may harbour personal grievances. Although coordinated communities such as right-wing or left-wing political activism and religious extremism continue to spread online, a huge number of competing and complementary ideologies are jostling alongside each other, all adding to the noise in the digital space. Environmental activism, gender rights activism, racial hatred, conspiracy theories and a multitude of grievance and identity-based ideologies are now common features of online communities. Their levels of effectiveness and disruptiveness vary hugely and they are less structured than their more traditional, politically anchored counterparts. Their spread is rapid and can have a significant impact on organisations, regardless of sectors. For instance, Extinction Rebellion in the UK gathered its followers via social media in April 2019 – primarily Facebook and Twitter – and within days organised significant protests across London. According to some estimates, in a short three days, the disruptive actions cost more than £12 million to businesses in the capital.

Beyond disruption – increasing instances of violence originating in the digital space have impacted organisations and individuals. Many societies have already experienced the exacerbation of political, racial and ideological grievances through the spread of mis-or-disinformation online. The pace at which this phenomenon can occur and the increasing number of channels available to it, makes online threat monitoring increasingly challenging.

A company’s public stance on an issue can rapidly be turned against them by a wide spectrum of actors in the digital arena. Casting a wide net and assessing the sentiment of a total population to infer how best to manage potential backlash is useful but can be highly challenging and miss discrete signals. On the other hand, detecting a direct threat against a company or an individual requires a more refined, precise and narrow scope of collection and analysis.

It should be noted here that adopting a legal and ethical approach to this type of monitoring and analysis is critical for security professionals. Considerations of free-speech, legal obligations and individual privacy concerns must be thoroughly undertaken ahead of any threat monitoring programs’ inception.

The challenge of behavioural analysis online

Behaviours online do not always mirror behaviours in the physical world. With the perception of anonymity, individuals online feel safe to develop extreme views and react emotionally to their environment – a phenomenon called deindividuation. Yet, despite language and signals that appear violent and threatening, action does not always follow. Faced with the wealth of information published online and limited resources, discarding false positives is a real challenge for analysts around the world. Online content displays many forms of non-standard grammar and irrelevant noises. Add to that the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation online and security teams can get overwhelmed by what to focus on.

The advances in text analysis, natural language processing and machine-learning have helped reduce the time to detect online threats and increase the time analysts can spend on analysis. Behavioural analysis provides tools to determine the motivation of threat actors and to help differentiate between those who merely threaten and those who are actively progressing toward an attack. However, behavioural analytics require a thorough understanding of the language universe actors evolve in, access to accurate and in-depth data and the time to produce a meaningful threat assessment. Together, human-machine cooperation for threat intelligence can help security teams in detecting and responding to emerging threats. For instance, researchers at Cardiff University in the UK studied cyber hate speech after traumatic events and found that a combination of human and machine analysis yielded significantly more positive results in assessing the credibility of threatening chatter than a purely technologically, or human-led approach.

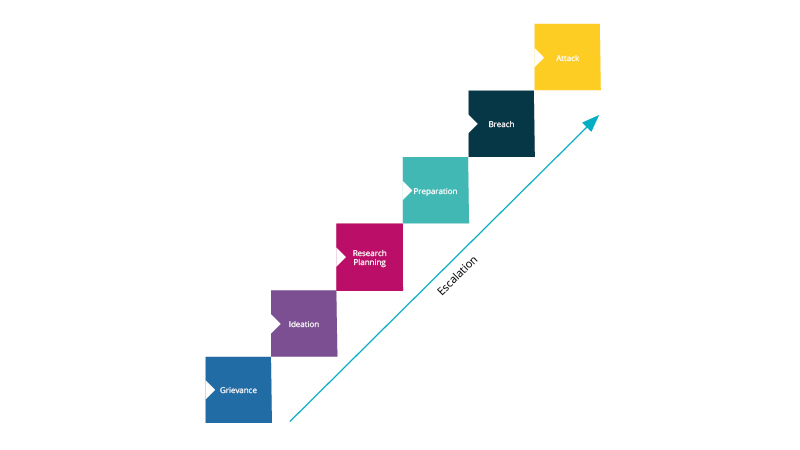

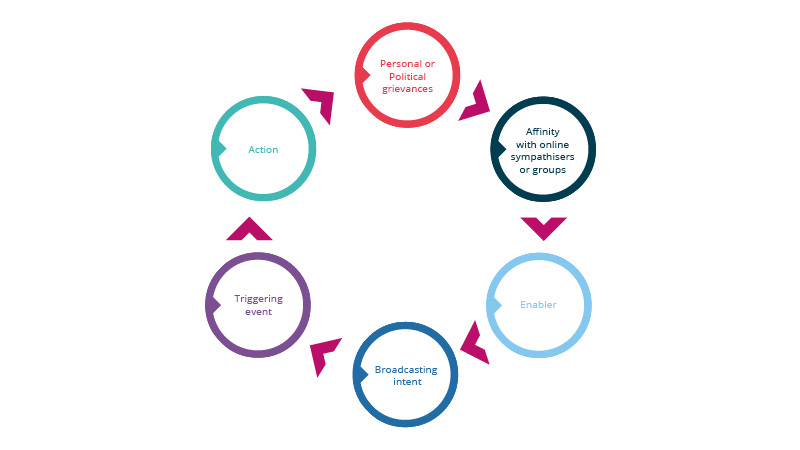

Behavioural studies on radicalisation and terrorism have developed models that are helpful to today’s security managers. Models can be applied to online threats detected in their early stages. They help to understand potential triggers and enablers that could suggest a step into action by individuals. The Pathway to Violence model, or the model for radicalization to terrorism, are examples which have helped public sector organisations assess the potential triggers for violent actions of individuals.

The search for identify-affirming ideologies that have the potential to justify grievances and recruitment by like-minded communities often feature as significant enablers and triggers for action. As security teams seek to monitor the environment thoroughly, conducting structured analysis of chatter and profiles can help determine the likelihood of threats spilling into the real-world.

- For instance, three linguistic factors – many more exist – can help security professionals assess the credibility of threatening online communications:

1. The resolution to commit violence, as evidenced by justifications, a demonstrated commitment of energy and effort, a lack of resiliency, and a disregard for consequences;

2. Intensity of effort as measured by frequency of contact, duration of contact, multiple means/methods of contact, and target dispersion;

3. Evidence of a personalized motive, as expressed directly or subtly through first-person personal pronouns, active voice, action verbs, etc.

These factors should be correlated and analysed as much as possible with an actor’s behaviour in the physical world. Past experience of incidents originating in online spaces demonstrated that an actor’s behaviour in the real world may differ significantly with their online behaviour, stressing the need for both of these to be considered in tandem when assessing a threat.

An organisational approach to online threats

Real-life examples of businesses’ successes and failures in responding to threats online underline the importance of security intelligence functions to identify threats in online spaces. As well as tactical support to security teams responsible for the management of company sites, cyber security, employee safety and high-profile events, online intelligence also provides valuable strategic insights for longer-term security strategies. The expansion of an organisation to new geographies; public relations management; technology roadmaps; and improving resilience and preparedness to external shifts in the environment can all benefit from rigorous online intelligence gathering.

1. Expertise must be dynamic and de-siloed: the rapid pace of change in online spaces means that a major role of security and intelligence functions is to keep on top of where the signals are coming from, and how they can be interpreted to support security actions. This requires investment in training and upskilling of teams. Expertise cannot remain within siloed teams and physical security, cyber security, technology and public relations teams must work together.

2. Online monitoring will always have limitations: businesses need to have a good understanding of the limitations of online monitoring and research, as well as the grey areas that exist when it comes to attempting to model intent and capability based solely on online sources.

3. Disinformation and misinformation online are rampant: they serve to motivate, radicalise and accelerate threats while creating significant noise for intelligence and security teams. Context remains crucial in producing joint human-machine online threat analysis. Organisations should ensure that their collection and analysis frameworks for security threats combines the real world and the digital world.

4. Behavioural analysis in the real world and online enhances machine-to-man cooperation: the formidable expansion of machine learning and automation in the security world should be leveraged through the application of behavioural analysis models, based on known previous incidents. The ultimate purpose of this cooperation should be to help differentiate between those who make a threat and those who pose a threat.

As with so much of threat monitoring, the quest for the fullest possible visibility of online threats entails a long hard look at an organisation’s internal structures and dynamics. Adopting the optimum organisational posture will enable an organisation's collective expertise to function at its best.