Analysis

Hydrogen – green superhero cleared for take-off?

- Global

- Social Risk and Compliance

Hydrogen – green superhero cleared for take-off?

Although hydrogen has been touted as a potential alternative to fossil fuels for almost half a century, it has only recently started to attract more concerted attention as governments rapidly seek to ramp up their decarbonisation efforts.

- A growing number of countries are producing national hydrogen strategies to provide long-term signals for investors and meet decarbonisation targets.

- The expansion of the hydrogen industry will happen gradually and at varying paces across regions, with the most commitment currently in Europe and pockets of the Asia Pacific region.

- The transition to a hydrogen economy will have significant geopolitical impacts by reshaping relations between energy exporters and importers.

- It will also pose a range of political, regulatory, operational, security and reputational risks to investors and operators.

Shades of green

Green hydrogen is increasingly recognised as key to overcoming the problem of how to store electricity produced by wind, solar and other renewable sources of energy. Electricity from renewable sources can be used to electrolyse water and separate the hydrogen from oxygen. The hydrogen can then be stored and reconverted into power as required, maintaining the stability of the electricity grid as it is weaned off hydrocarbons and alleviating the challenges posed by the intermittency and seasonality of renewables.

However, reaching net zero greenhouse gas emissions will require more than a massive expansion of power generated by renewable sources and there is growing pressure for decarbonisation across all sectors of the economy. Electricity still accounts for less than a quarter of final energy consumption globally, and it is widely considered that hydrogen – as a fuel or in derivative forms such as ammonia – will play a part in decarbonising industries where electrification is more difficult. “Harder-to-abate” sectors that are likely to be targeted include steel, chemicals, shipping, aviation and other long-haul transport and road freight, as well as domestic heating.

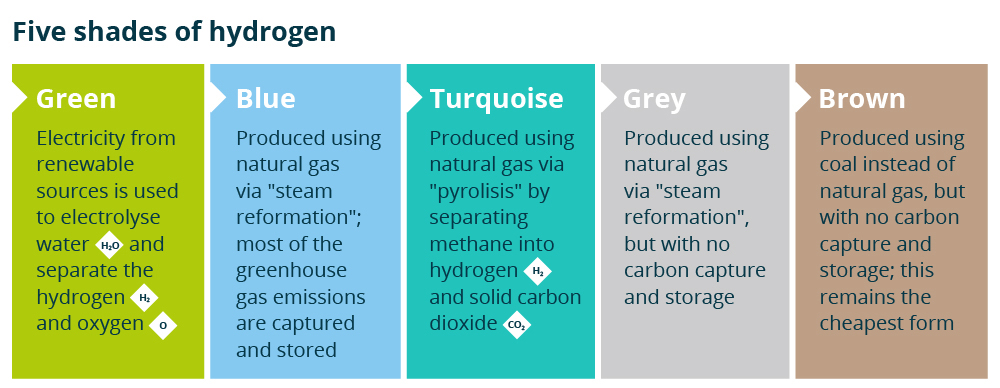

Despite hydrogen’s potential to accelerate decarbonisation, most hydrogen produced today is of the so-called grey polluting variety. The least polluting green variety makes up a tiny proportion of current production and is typically approximately two or three times more expensive than even the relatively costly blue alternatives. The plummeting costs of renewables over the last decade, however, have brought cost parity within reach. Further reductions in the cost of renewables as well as electrolysis will be needed to make green hydrogen truly competitive with the blue variant – likely by about 2030 according to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Regional differences

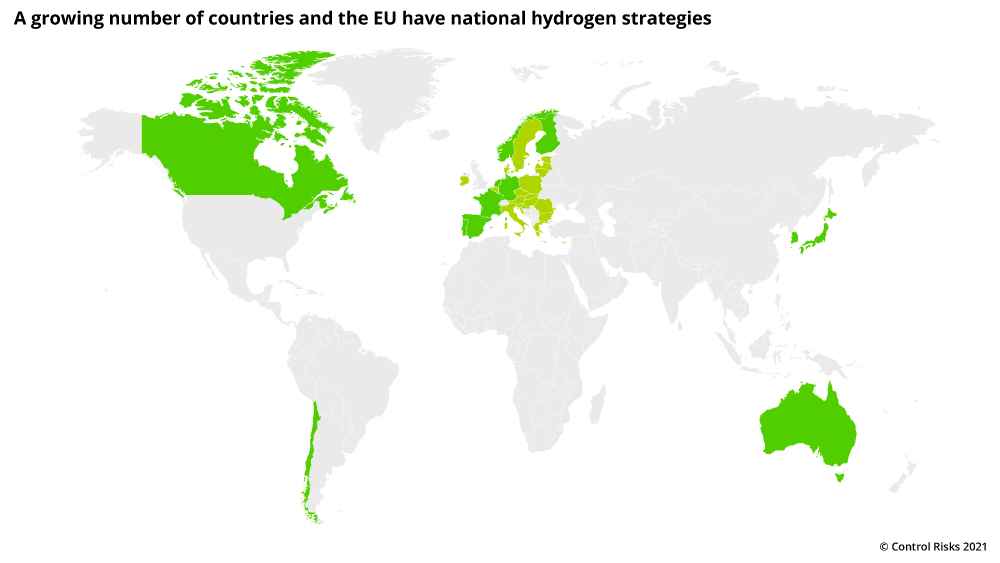

A growing number of countries (and some sub-national governments like the US state of California) in the last two years have developed hydrogen strategies. Many of those that have produced such strategies have also made long-term commitments to carbon neutrality – this appears to be no coincidence given that hydrogen is seen as key to reaching this target.

Europe sits at the epicentre of most hydrogen projects today and European governments are also leading the way in developing hydrogen strategies. Since 2018, France, the Netherlands, Germany, Portugal, Spain, Finland, and Norway have all produced domestic strategies. The EU in mid-2020 published one for the bloc. Governments in Asia Pacific – the region with the second largest number of hydrogen projects – have also developed strategies (Japan, Australia, South Korea). Others in the region have outlined a broad vision or are investing in research and development.

In part, the intent of such strategies is to support innovation and to provide long-term signals for investors, especially while costs for green (and blue) hydrogen remain higher than for more polluting variants and while a market for the product remains nascent.

These strategies are similar, though with some differences. Europe has focused on green hydrogen – the EU intends to produce 40 GW by 2030, which is supported by targets enshrined in the strategies of some of its members including France (6.5 GW), Germany (5 GW), Spain (4 GW), the Netherlands (up to 4 GW) and Portugal (2 GW–2.5 GW). Others in Asia have included targets for fossil fuel-based alternatives or a combination of different types.

The strategies also differ in terms of their targets. Most of those focusing on green hydrogen have included electrolysis capacity targets or focus on slashing the costs of production. Australia’s “H2 under 2” target aims to bring the cost of green hydrogen below AUD 2 (approximately USD 2) per kg – in other words, to a cost at which it can compete with polluting alternatives. Chile’s strategy has a target cost of USD 1.5 per kg by 2030. Some strategies focus more on domestic decarbonisation, while others (including notably Australia, generally considered a laggard on climate action) are also aiming to scale up production for export.

Most policy support for hydrogen has focused until recently on the transportation sector, particularly road freight. However, national strategies will also promote the use of hydrogen across different harder-to-abate industries.

More countries are also expected to come forward with hydrogen strategies in the year ahead. According to IRENA, these will include other European countries like Austria, Denmark, Italy and the UK, as well as Colombia, Morocco, Oman, Paraguay and Uruguay. Other countries that have produced net zero emissions targets will likely follow suit.

Geopolitics of hydrogen

The growth of the green and blue hydrogen industries will have significant geopolitical consequences in reshaping relations between traditional energy exporters and importers. In many regions, the growth of liquefied natural gas (LNG) and blue hydrogen to replace coal in power generation and residential heating will be a more viable route for reducing emissions in the next decade than an expansion of green hydrogen.

More advanced economies, particularly in Europe, are more likely to transition directly to green hydrogen and therefore reduce their demand for natural gas in generating power or supplying transport fuel. This will result in a significant reduction in gas and gas by-product demand with significant financial implications for key suppliers like Russia, Algeria, Nigeria and Qatar.

Given that hydrogen will also gradually replace gasoline as fuel for some freight transportation its adoption will accelerate the collapse in oil demand in advanced economies, again impacting some vulnerable oil exporters, like Iraq, Libya and sub-Saharan African producers. If demand for blue and turquoise hydrogen declines again quickly on a global scale, it will create more severe problems for fossil fuel economies, including by increasing economic and political instability, irregular migration and insecurity.

On the other hand, the growth of hydrogen will create opportunities for traditional energy importers to generate greater energy security. Some fossil fuel producers too are actively looking to leverage existing natural gas pipelines for exporting hydrogen in order to retain their share of energy markets. For example, major fossil fuel exporters like Russia and Algeria have large unpopulated territories that can be leveraged to produce green hydrogen via new solar and wind capacity.

However, some may struggle to sustain their share of energy markets, particularly as importers in regions such as Europe are viewing the transition to hydrogen as the safest route to enhance their energy security and to reduce dependency on a dominant supplier, like Russia. As all EU countries with renewable energy capacity and water resources will be able to set up domestic production of hydrogen, they will resort to imports only to supplement domestic capacity or to take advantage of a lower price.

The hydrogen transition is also likely to lead to an increase in stranded assets in different parts of the world where existing investments in fossil fuels, including natural gas and LNG, may become unprofitable. Financial markets are already discounting long-term investments in fossil fuels. This transition will disproportionally affect investments in developing countries.

Risks to investors and operators

As well as impacting geopolitics, the growth of the hydrogen industry will pose a range of political, regulatory, operational, security and reputational risks to investors and operators:

- Policy commitments and incentives as well as regulatory obstacles to the expansion of renewables will impact the prospects for green hydrogen given that cost competitiveness will require a continued fall in the costs of renewables such as wind and solar.

- Carbon pricing and other regulatory frameworks (that are likely to become more common) have the potential to cut demand for polluting alternatives and raise the competitiveness of green and blue hydrogen and derivative products.

- Regulatory frameworks will vary from country to country, particularly as governments pursue different solutions for deep decarbonisation. Opposition from interest groups and decision-makers is likely to create delays in the implementation of national strategies. And different approaches will lead to a range of opportunities and risks across hard-to-abate sectors.

- Climate activists will increasingly scrutinise the hydrogen sector, particularly as it is scaled up and hydrogen is traded across borders. Some will accuse firms of greenwashing as they expand investments in anything other than the green variant.

- Opposition from local communities will likely stem from the expansion of infrastructure, the use of scarce clean water resources and concerns about health, safety and environmental (HSE) risks in the large-scale production and transportation of toxic, explosive and corrosive hydrogen derivatives.

Outlook

As countries start to identify how they intend to meet their long-term decarbonisation targets, hydrogen is likely to play a big part. Exactly what part it plays is still to be determined and will vary by region. Comprehensive risk analysis, scenario planning and regulatory forecasting will be essential to understanding the risks and opportunities that this will create.